A golden Easter Night, bright as day? Does that sound like a paradox to you? In our newest blogpost, Marlene Schilling, Dphil student at Oxford University, discusses the fascinating use of personification within a newly discovered Medingen manuscript.

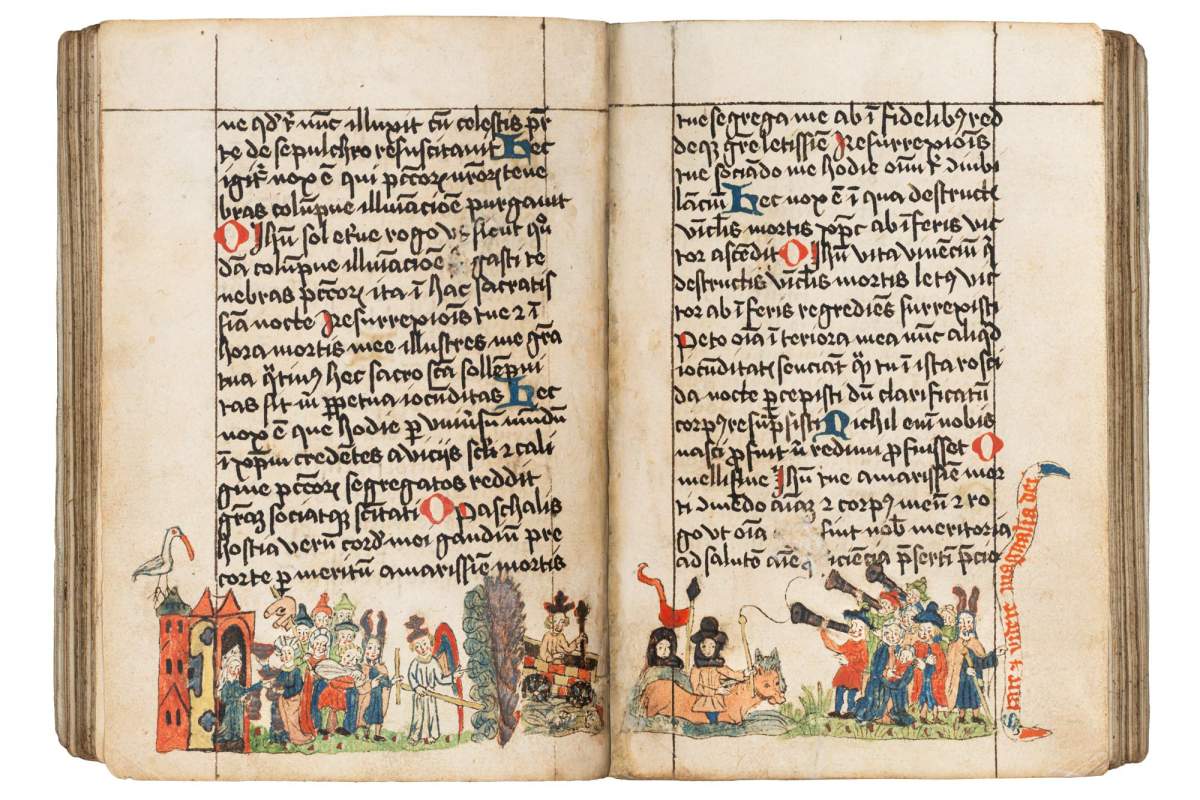

Prayerbook for Easter. Manuscript in Latin and Low German. Northern Germany, Kloster Medingen, between 1467 and 1479. Moses leading the Isrealites out of Egypt, fol. 2v-3r.

Right at the beginning of this recently discovered Easter prayer book from Kloster Medingen, we find a stunning illumination spanning over two pages. What initially looks like a slightly chaotic scene, with two groups of people, a carriage, an angel, and a man with weird donkey ears, actually depicts the Exodus from Egypt in several snap-shots. The weird ears are actually Moses’ horns, an attribute he received due to a mistranslation. On the left side, he is seen parting the Red Sea for his people with the help of an angel, following the guidance of a fiery pillar by night and a cloud by day, here shown as a bipartite column. The Egyptian army tries to follow the Israelites through the parted Red Sea; the crowned Pharaoh in his carriage drives into the centrefold while the soldiers on their horses drown (on the right side). The Israelites rejoice and celebrate their flight, blowing their trumpets at the defeated Egyptians while Moses leads his people out of the double-spread into their new future.

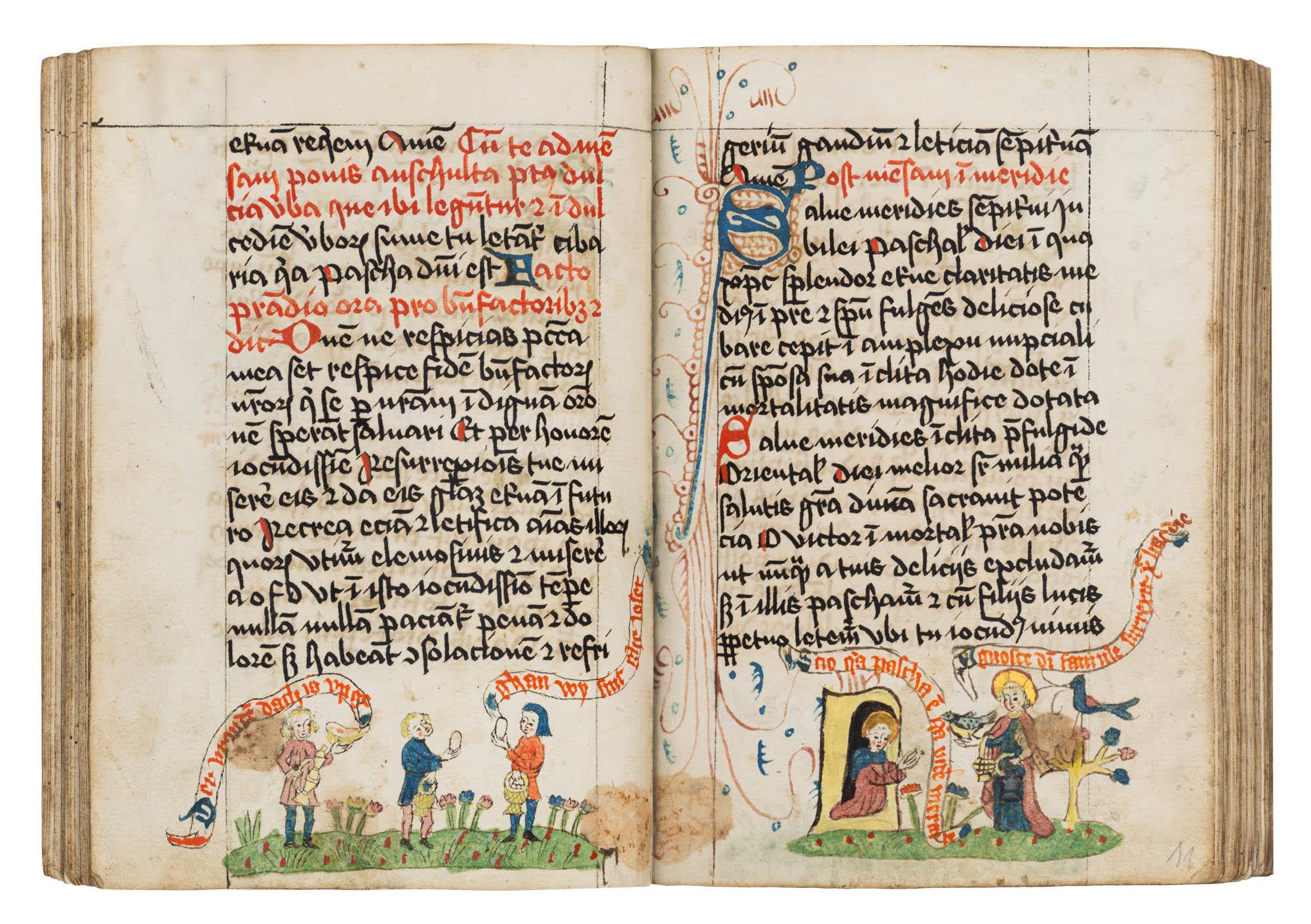

Detail of a young man with a flower crown and singing We schollen allen vrolik sin to desser oster[osterliker tijd]. Prayerbook for Easter. Manuscript in Latin and Low German. Northern Germany, Kloster Medingen, between 1467 and 1479. fol. 114v.

Three boys celebrating Easter. The one on the left holding a carafe of wine and a fish, while the boys on the right are holding baskets with eggs. Prayerbook for Easter. Manuscript in Latin and Low German. Northern Germany, Kloster Medingen, between 1467 and 1479. fol. 107v.

This intrinsic connection is highlighted in the Exsultet prayer, directly referencing the Exodus. The oldest prayer of the Roman Missal is a commemoration and celebration of the Easter night, the moment of the miraculous Resurrection that granted mankind forgiveness for their sins. As our manuscript misses its first quire, the text begins in the middle of the Exsultet, which, as is typical for Medingen prayerbooks, enhances the prayer with additional reflections. The illumination can be seen as such a reflection, due to the reference to the Exodus, “Hec nox est, in qua primum patres nostros, filios Israel, eduxisti de egypto, quos postea mare rubrum sicco vestigio transire fecisti” (This is the night in which you first led our fathers, the children of Israel, out of Egypt, those whom you late made cross the Red Sea with dry steps), being placed on the previous page, leading up to the scene.

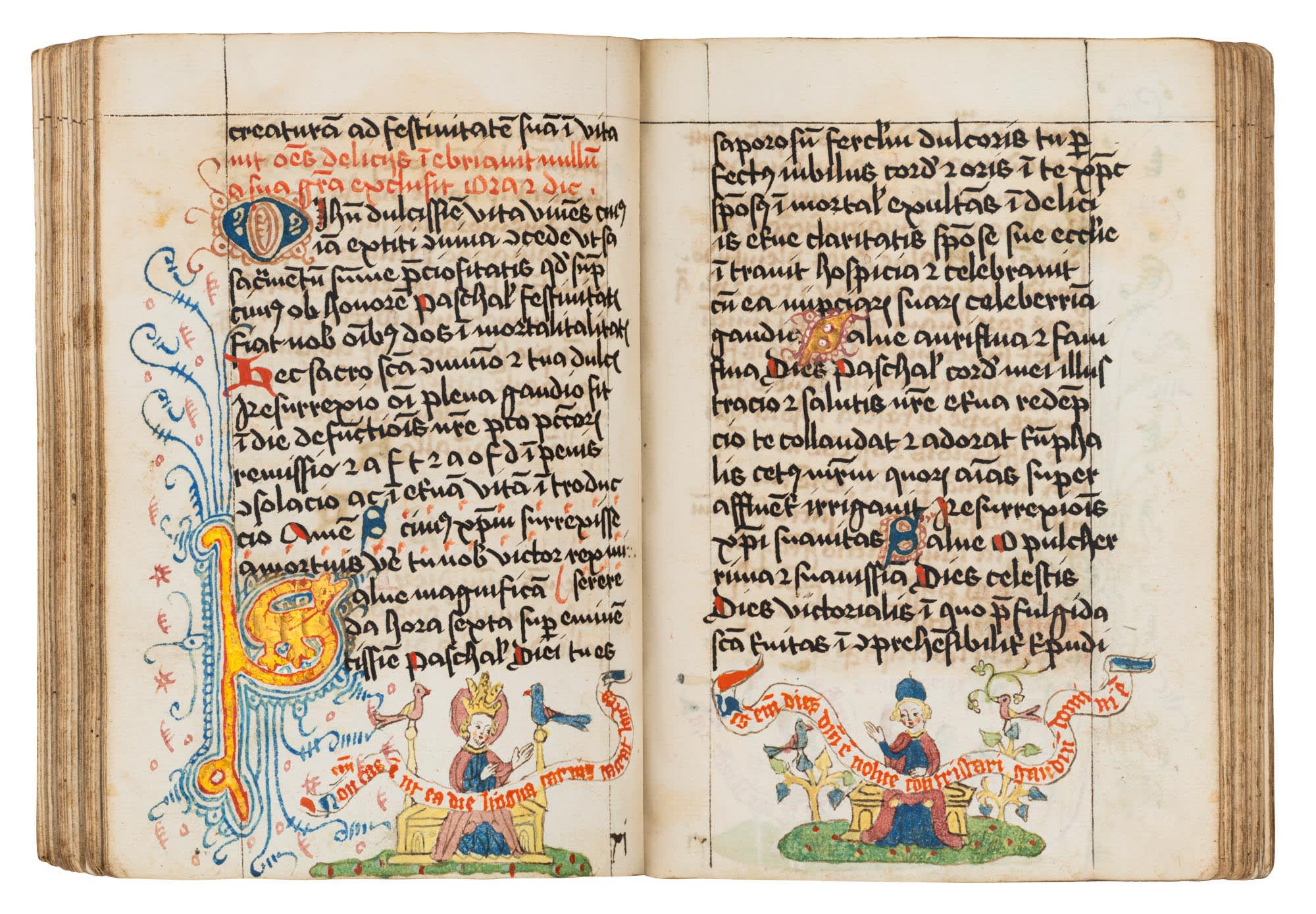

Pope Gregory on the left and a male marginal figure on the right. Prayerbook for Easter. Manuscript in Latin and Low German. Northern Germany, Kloster Medingen, between 1467 and 1479. fol. 103v-104r.

The Exsultet features a reflection on the night as moment of the Resurrection of Christ: “O vere beata nox, que sola meruit scire tempus et horam, in qua Christus ab inferis resurrexit!” (O truly blessed night, which alone deserved to know the time and hour in which Christ rose from the underworld!). The night as an inanimate concept is understood as human, attributing human qualities like knowing to it. This ‘personification’ is a particular stylistic device that is used throughout the prayer book, even beyond the context of the Exsultet prayer. One very telling example, also reflected in the manuscript’s splendid decoration, can be found on fol. 26v, greeting the night as ‘gold flowing’ (auriflua) and as ‘the highest’ (altissima).

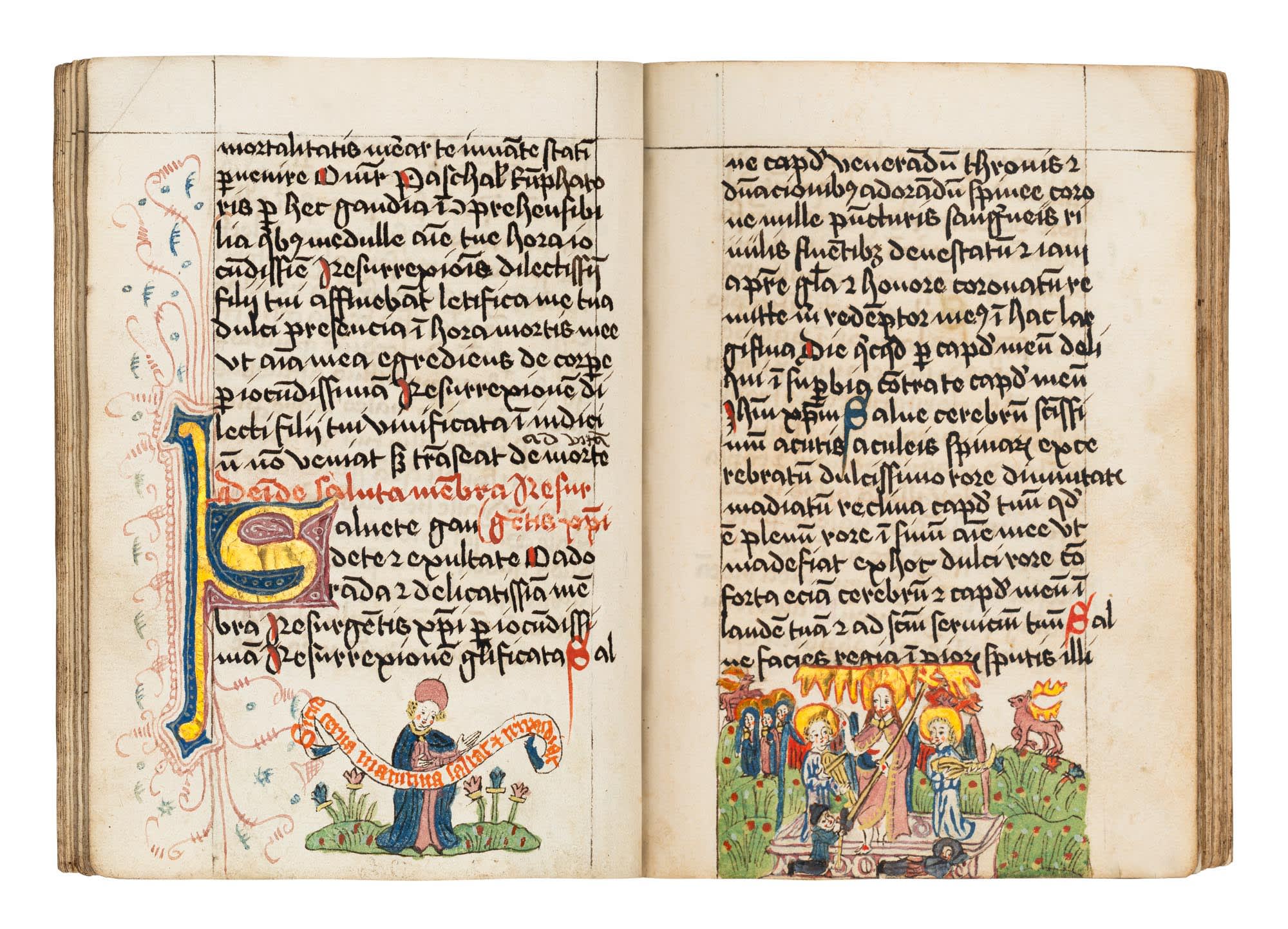

Resurrection Scene on the right. Christ standing under the rays of the Easter sun atop the tomb flanked by angels. In the background the three Marys approaching and two stags with gold horns. Prayerbook for Easter. Manuscript in Latin and Low German. Northern Germany, Kloster Medingen, between 1467 and 1479. fol. 68v-69r.

It is important to remember that prayer books like ours were used during the liturgical mass of Easter night, in the factual darkness between Holy Saturday and Easter Sunday, in a church, where the candle light was reflected in the golden initials of the prayer books, actually showing, the paradox of a golden light-filled Easter night. This imbibes the recipient of those manuscripts, in our case most likely a nun from the Medingen convent, with an important role, as the opening of the book ultimately gives life to this manifestation of the golden Easter night.

As a little side note: We have a very good idea, how the congregation looked like in which the prayer book was probably used: On fol. 133v we see a group of nuns led by a provost and a group of lay people taking leave of a similarly personified Easter Day, visualised in the little smiling face of the golden (if due to oxidation very silver looking) sun.

But why were personifications like this used in the context of a Late Medieval Easter prayer book? The literary device of personification enables the person at prayer to talk about and reflect on Easter in a very tangible way. Understanding the Easter night as a person allows the nun to directly greet and address the entity which aids in creating an intimate relationship with this particular moment in time and all its implication for salvation. The personification creates a vehicle for a transcendent and intangible idea, making an otherwise literally invisible concept visible.

This brings us back to the initial illumination depicting the Exodus. This illumination is also a way of emphasising and a means of making visible, as it highlights the relations between Easter and the New Testament on the one hand, and the Exodus and the Old Testament on the other. This fascinating approach can be understood as an internal strategy within the prayer book to make abstract concepts, like those relations between the Old and the New Testament or the Easter Miracle and Easter, more understandable and palpable. It is about making the transcendental tangible, manifesting the divine – and our manuscript is a prime example of those efforts.

Marlene Schilling is a doctoral student at the Faculty of Medieval and Modern Languages at Oxford University, after graduating with a MSt in Modern Languages (German) from Oxford and an MA in German Literature from the University of Tübingen. Her dissertation, ‘Personification as Devotional Strategy in Middle Low German Literature’ focusing on the use of personification within the Medingen manuscripts, is supervised by Prof. Henrike Lähnemann, Chair of Medieval German Literature and Linguistics at Oxford. Marlene is also the co-founder of the Oxford based Medieval Women's Writing Research Group focusing on supporting students and young academics in engaging with women's writings by hosting regular lectures and research seminars.

Academia: https://oxford.academia.edu/MarleneSchilling

Twitter/X: https://twitter.com/malu_schilling

Selected Bibliography/Further Reading

Bynum, Caroline Walker: Dissimilar similitudes: Devotional Objects in Late Medieval Europe. New York 2020.

Fuchs, Guido/Weikmann, Heiko Martin: Das Exsultet. Geschichte, Theologie und Gestaltung der österlichen Lichtdanksagung. 2nd edition. Regensburg 2005.

Huber, Christoph: Artikel „Personifikation“. In: Jan-Dirk Müller [u.a.] (Hgg.): Reallexikon der deutschen Literaturwissenschaft. Band III P–Z. Berlin/New York 2007 [reprint], pp. 53–55.

Lähnemann, Henrike: “Manuscripts.” Medingen Manuscripts. Henrike Lähnemann, St. Edmund Hall, University of Oxford. http://medingen.seh.ox.ac.uk/index.php/manuscripts/. Last accessed: 15.03.2024.

Lähnemann, Henrike: Bilingual Devotion in Northern Germany: Prayer books from the Lüneburg Convent. In: Elizabeth Andersen/Dies./Anne Simon (Ed.): A Companion to Mysticism and Devotion in Northern Germany in the Late Middle Ages. Leiden/Boston 2014, pp. 317–341.

Uffmann, Heike: Inside and Outside the Convent Walls: The Norm and Practice of Enclosure in the Reformed Nunneries of Late Medieval Germany. In: The Medieval History Journal (2001), Vol. 4 (1), pp. 83–108.

Wahle, Stephan: Reflections On The Exploration Of Jewish And Christian Liturgy From The Viewpoint Of A Systematic Theology Of Liturgy. In: Albert Gerhards/Clemens Leonhard (Ed.): Jewish and Christian Liturgy and Worship. New Insights into its History and Interaction. Leiden/Boston 2007, pp. 169–184.