Basel as a cultural city in the late Middle Ages

From the High Middle Ages onwards, the city of Basel was an important economic centre (for long-distance trade and guilds) on the southern Upper Rhine. The cultural importance of the city was also reflected in its close contacts with neighbouring cities such as Strasbourg and Freiburg.

The readers of our blog post might know that Basel University was founded in 1460, making it one of the oldest universities in Europe and the oldest in Switzerland. A few decades earlier, in 1433, the first paper mill was established in the city by the wealthy councillor Heinrich Halb(e)isen outside of Riehentor. Twenty years later, further paper mills were built, including the one in the St Albans Graben, which can still be visited today as a paper museum.

Basel's convenient position directly on the Rhine quickly raised the city to the rank of an internationally frequented trading metropolis. Basel is also the city where the first public museum — the Amerbach Cabinet — was accessible to the public as early as 1677. Thus, Basel is also a pioneer city in cultural aspects. Until today, Basel has remained true to this tradition and is home to approximately forty museums. Moreover, it qualifies as an international cultural capital thanks to one of the most important art events, the annual Art Basel, which is perhaps the most important contemporary art fair in the world.

Basel as the centre of book printing

This blog post, however, will focus on Basel as a key place for the early printing press. Since we specialise in precious books from the Middle Ages and the Renaissance (handwritten as well as printed) we would like to draw your attention to some of Basel’s early printed books.

Printing with movable type, which Johannes Gutenberg established in Mainz around 1455 was one of the watershed moments of modern times. Like Basel, the city of Mainz is located on the Rhine; this river has always been important route through Europe where people, goods, and ideas travelled.

The first printer to settle in Basel was Berthold Ruppel, an early assistant of Johannes Gutenberg in Mainz. He learnt the new "black art" at first hand from his master. According to the sources, he originally came from Hanau, which probably did not refer to the town in present-day Hesse, but to Hagenau in Alsace. During Gutenberg's legal dispute with Johannes Fust, which ultimately ruined him financially, Ruppel stood faithfully by his boss. But when the case was lost, he moved up the Rhine closer to his old native town. He may have stopped in Strasbourg before coming to Basel, as this city was also an important centre for printers.

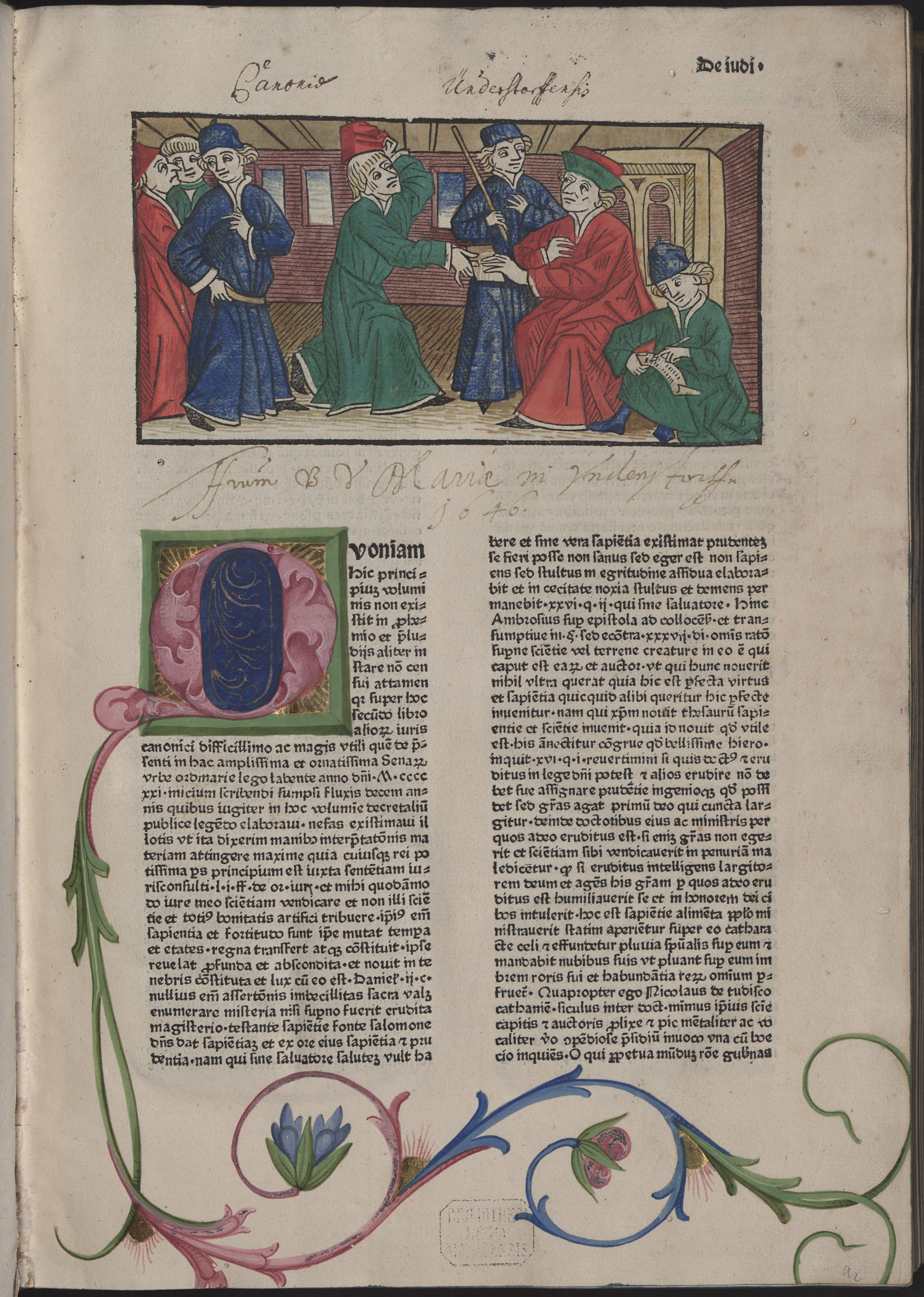

Ruppel must have been active in Basel from around 1468 and gained citizenship in 1477. He made a considerable fortune through his trade early on, as can be deduced from his taxes. Later, he also specialised in book and paper trade, which was quite common for printers. He focused on theological textbooks in Latin, i.e. works that were used at university and in monasteries. In a joint project that he carried out with Michael Wenssler and Bernhard Richel in 1477 (GW M47806), there are a few woodcuts, but the six-volume print was a commercial failure.

The aforementioned Michael Wenssler came from Strasbourg and enrolled at the University of Basel in 1462. Like him, most printers had a master's degree, as the printing trade could not be practised without an elaborate education. In the prologue to one of his printed works (GW 3676), Wenssler chose proud words to emphasise Basel’s standing as a printing metropolis. He postulates that 'Mainz may have invented the art of book printing, but Basel pulled it out of the mud' (Artem pressurae quanquam moguncia finxit, E limo traxit hanc basilea tamen). This definitely sounds haughty from today's view, but the printer’s pride in his own craftsmanship should probably be forgiven.

Both Ruppel and Wenssler were initially enormously successful, but after a while both had to face financial difficulties, which forced them to leave the city eventually. This has, sadly, often been the printers’ fate, since not every workshop had a patron or a sponsor to pre-finance editions. Hence, the economic risk often lay solely with the printers and if the books did not sell as hoped, it could mean financial ruin.

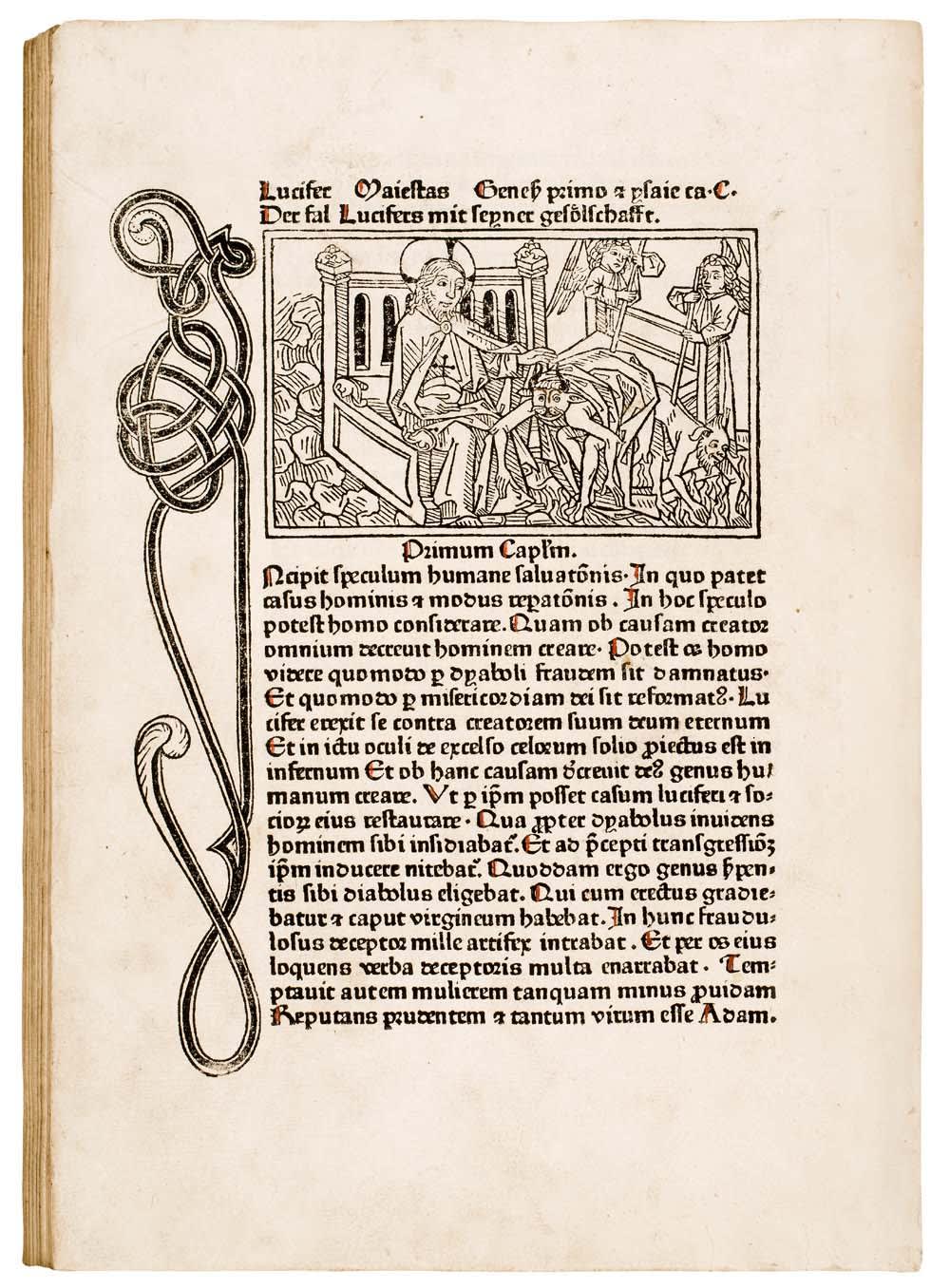

Our third printer already mentioned above, was Bernhard Richel. He was responsible for a richly illustrated book with imaginative woodcuts. The impressive folio volume of the Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Salvation) was printed in 1476 (GW M43016).

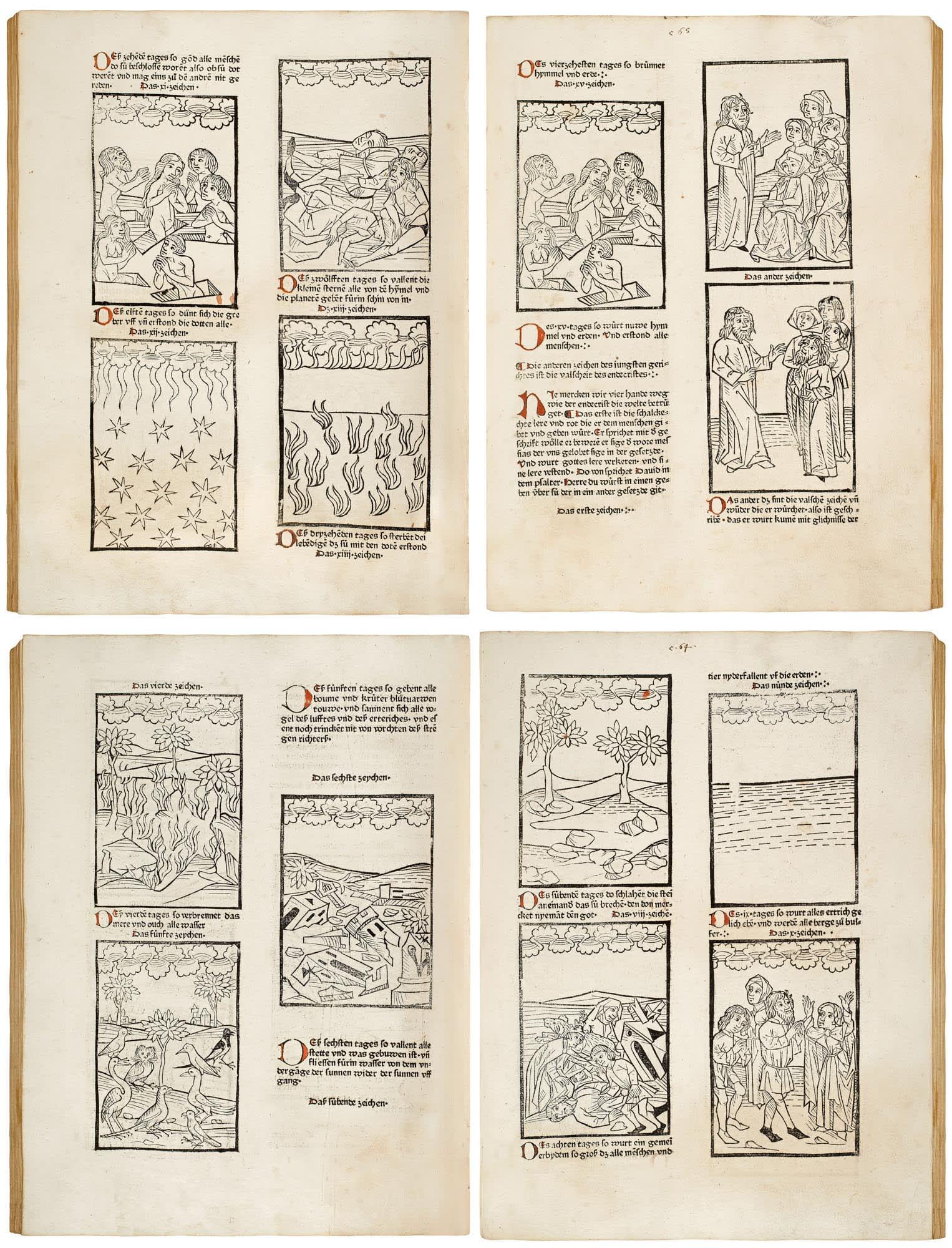

Richel’s Speculum shows an astonishing artistic maturity which elevates this work to the rank of Basel’s most important illustrated incunable. The text that accompanies the countless illustrations was written around 1324 by a Dominican monk. It was once suggested that Ludolph of Saxonia was the author, but this assumption has now been rejected. The real eye-catcher are the inventive and unusual illustrations. It has often been claimed that medieval people needed images because of their inability to read. This is only part of the truth. In fact, most people, who were in the position to buy a manuscript or a printed book had a good education. Still, they appreciated images to accentuate the meaning of the texts, and to aid them in their contemplations.

Richel’s cuts are expressive and in the stylistic traditions of the Upper-Rhenish and Alsatian artworks. Maybe an Alsatian manuscript – similar to Munich’s, BSB, clm 146 – served as a model for the designs, since we can observe many iconographic parallels. Three different draughtsmen were likely responsible for the designs of our woodcuts. Their work constitutes a major contribution to our understanding of late medieval illustration. Interestingly, Martin Huss from Basel, who went to work in Lyon re-used Richel’s blocks for the French Mirouer de la Rédemption of 1478.

The next book is not printed in the city of Basel but in the near-by city of Freiburg im Breisgau. The author/printer Friedrich Riederer created a monumental and crucial work on rhetoric in German (GW M38173); an unusually early scholarly approach to the topic. What connects the incunable with Basel are above all the woodcuts, two of which show the artistic influence of Albrecht Dürer.

The great Nuremberg artist Albrecht Dürer had been travelling to improve his knowledge and craftsmanship on art in Colmar. He had intended to meet his role model, Martin Schongauer, but when he arrived in Alsace, he heard of the passing of Master Martin. Thus, he went to Basel, where he was involved in the illustration of several printing projects. He had gained experience in the workshop of Michel Wolgemut, where he had been trained in the art of woodcut illustration for Nuremberg Master’s large book projects under the tutelage of his godfather, Anton Koberger.

Sebastian Münster, Cosmographei...Basel, Heinrich Petri, 1550, Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books, Basel

We hope that you enjoyed our blogpost. We wish you all a wonderful Advent time!

Dr. Jörn Günther and team