Nuremberg at the end of the 15th century, was one of the most bustling and industrious cities in Europe. With its vibrant art scene, its flourishing industrial areas, and devotional activities throughout the city, it attracted many visitors. From far, travellers would recognize the towers of St. Lorentz's and St. Sebald's, the two most important parish churches of the town that were also highlighted in Hartman Schedel's world chronicle (Nuremberg, 1493).

Schedel's Chronicle was financed by Sebald Schreyer and his brother-in- law, Sebastian Kammermeister. Schreyer, in particular, was involved in various book productions.

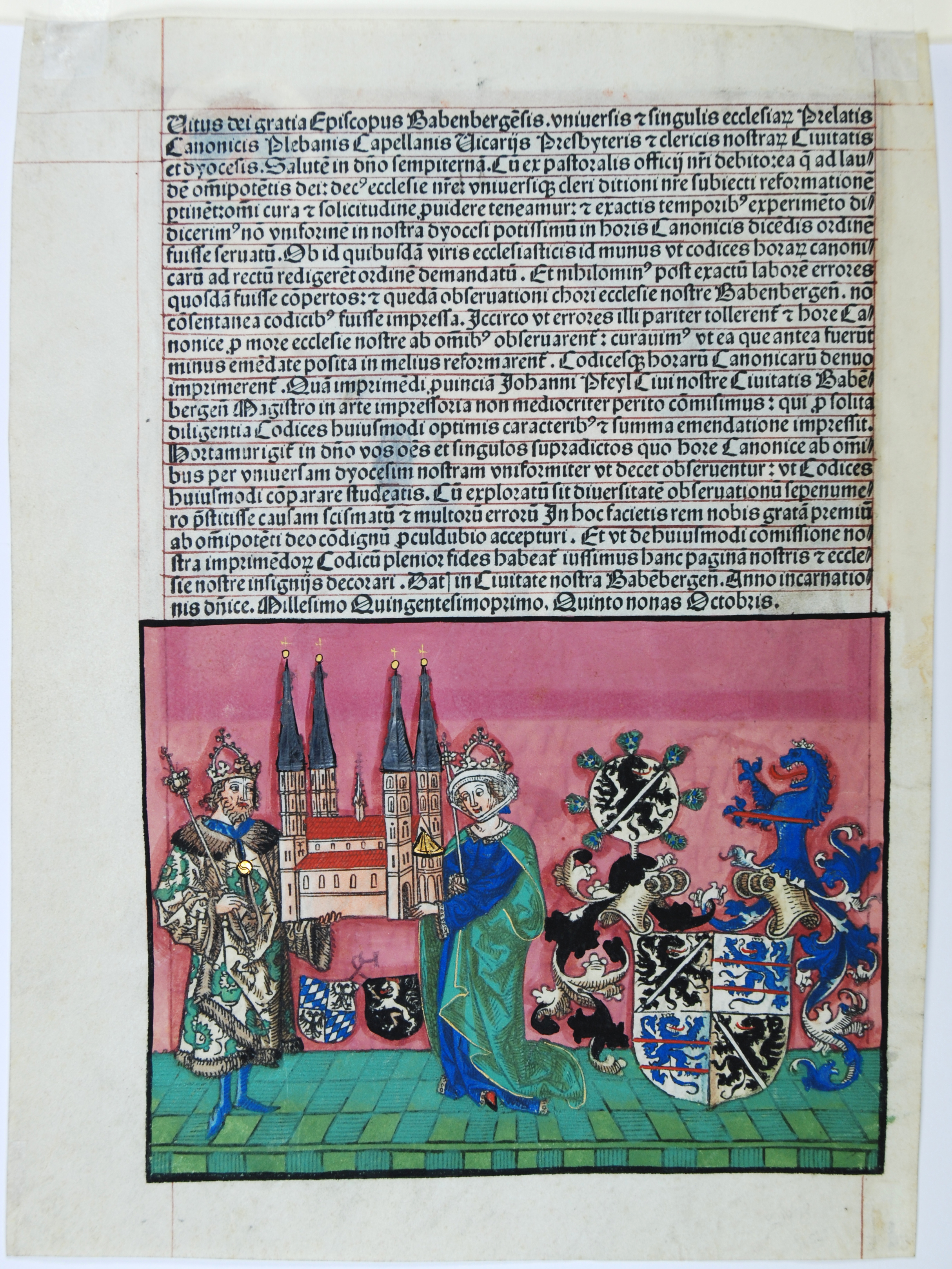

Nuremberg's burghers prodigiously fostered the cult of Saint Sebald who is represented on our miniature as a pilgrim with a model of his church, and flanked by two donors.

The donors are two leading citizens, identified as Paul Volckamer (d. 1505, left) and Sebald Schreyer (d. 1520, right), tutor and custos of St. Sebaldus Church in Nuremberg respectively. The men commissioned various works of art for their parish church that was a major pilgrimage site. Schreyer is the more interesting of the two, since he also took the initiative in several printing projects. First, in 1484, he commissioned two breviaries to be printed on vellum in Bamberg by Johannes Sensenschmidt and Heinrich Petzensteiner. They were then illuminated and bound in Nuremberg and 'in die kirchen der gemein pristerschaft darauss zu peten gelegt'. Six years later, again in Bamberg and again printed on vellum, he ordered 21 Missals. To six of these he added a hand-painted portrait of St. Sebald, flanked by himself and Volckamer. Again, in 1496, the memoria illustrations were added to the blank recto of the Canon illustration, so that the priest would see it every day when he used the book.

Five years later, in 1501, Schreyer ordered new books in Bamberg, this time Breviaries. Again, similar pictures were added, but now on the title page, to the blank recto of the printed authorization on the verso.

Sebald Schreyer (1446-1520) had studied in Leipzig. In the service of Emperor Frederick III he was awarded a coat of arms. In 1475, he relocated to Nuremberg. Over the years, his wealth grew. He became a member of the town council and a church warden in St. Sebald’s.

As a strong promotor of the arts and sciences, Schreyer stimulated and sponsored important printing projects at a time when Nuremberg was the centre of German humanism. He is well-known for his participation in the complex and costly printing of the world chronicle by Hartmann Schedel (1491-1493). For the 'making of' Schedel's Liber chronicarum, he and his brother-in-law Sebastian Kammermeister signed a contract with the printer Anton Koberger, and the illustrators Michael Wolgemut and Wilhelm Pleydenwurff (a copy of the first edition in German with their painted coat of arms is preserved in Berkeley, USA).

Earlier, Schreyer had persuaded Sigismund Meisterlin to write a new Sebaldus legend (1483) and in 1488, he supported Meisterlin's bilingual Nueronbergensis Cronica (and inserted a part of his own family history). Over the years, Schreyer supported several more projects, amongst others an ode to St. Sebald (1493), in cooperation with his friend, the humanist Konrad Celtis (1459-1508), published on a (nowadays rare) broadsheet illustrated by Albrecht Dürer.

In recent years, scholars have paid increasing attention to medieval memorial culture, since monuments and other works of art were made to honour the dead and to stimulate their liturgical remembrance. The memoria and commemorative practices were linked to all aspects of medieval society. In Nuremberg, Sebald Schreyer played the most interesting role in all this. Not only for himself and his wife, but also for his brother-in-law Konrad Topler as well as for the patrician Georg Keipper, Schreyer (and other citizens) took care of memoria foundations.

For ‘everlastig’ memoria, the Schreyer-Landauer epitaph-relief on the outside of the eastern choir of St. Sebald (1490) was created – representing the family relations of Schreyer and his cousin, including their parents and children. This was the first major order for the sculptor Adam Kraft (d. 1509).

These works of art were made to obtain salvation and perpetuate the donor’s memory, so that the bond between the living and the dead would not break. All this puts Schreyer and the fine miniature at hand in perspective: The more one invested in the liturgical remembrance, the more one would participate in commemorative rituals carried out by parish priests in order to attain salvation of the soul.

See also: Heiligen und Hasen. Bücherschätze der Dürerzeit ed. by Thomas Eser and Anja Grebe. Nuremberg 2008