For centuries, books have been written to share knowledge, inspiration, and discoveries. What many of us may not realize is that the Middle Ages determined what texts were handed down from Antiquity onwards. Had it not been for the scribes and patrons of late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, the entire literature of Greece and Rome would have perished. Medieval illuminated manuscripts gave stature to these ancient texts and thus contributed, to a large extent, to their preservation.

Last November, Stephen Fry, the famous British comedian, actor, long-time quizmaster, as well as successful author, published a retelling of stories that the ancient Greeks invented about the birth of the universe, their gods, and the creation of humankind (Michael Joseph - Penguin Books 2017).

As a child, Stephen Fry fell in love with these stories, which have never left him since. His lively, funny, and erudite book conveys this passion for Greek-Roman myths, which the author shares with numerous predecessors as well as contemporaries. One such a "predecessor" is the Flemish bibliophile, Raphael de Mercatellis, and here we present a medieval illustration from his library that attests to a myth also in Fry's book (we give here only the Latin names, not those in Greek).

Fry is an audacious storyteller who lets us experience the adventures of the Gods and the torments and punishments of traitors and others. He thoroughly enlivens the old stories, including the extra marital affairs of Zeus/Jupiter, King of the Gods. One of these stories tells how Pallas Athena was born: "from the cracking open of the God’s great head" – as Fry relates:

“The onlookers held their breaths as slowly there arose into view a female figure dressed in full armour… Equipped with plated armour, shield, spear and plumed helmet, she gazed at her father with eyes of a matchless and wonderful grey. A grey that seemed to radiate one quality above all others – infinite wisdom” (Fry 2017, o.c. pp. 84-85).

As of old, the story recounts that Metis, who just had conceived by Jupiter, transformed herself into a fly, but then was eaten – with any child that was possibly forming in her womb – by Jupiter, who had taken the form of a lizard, all without Jupiter’s wife Hera having noticed.

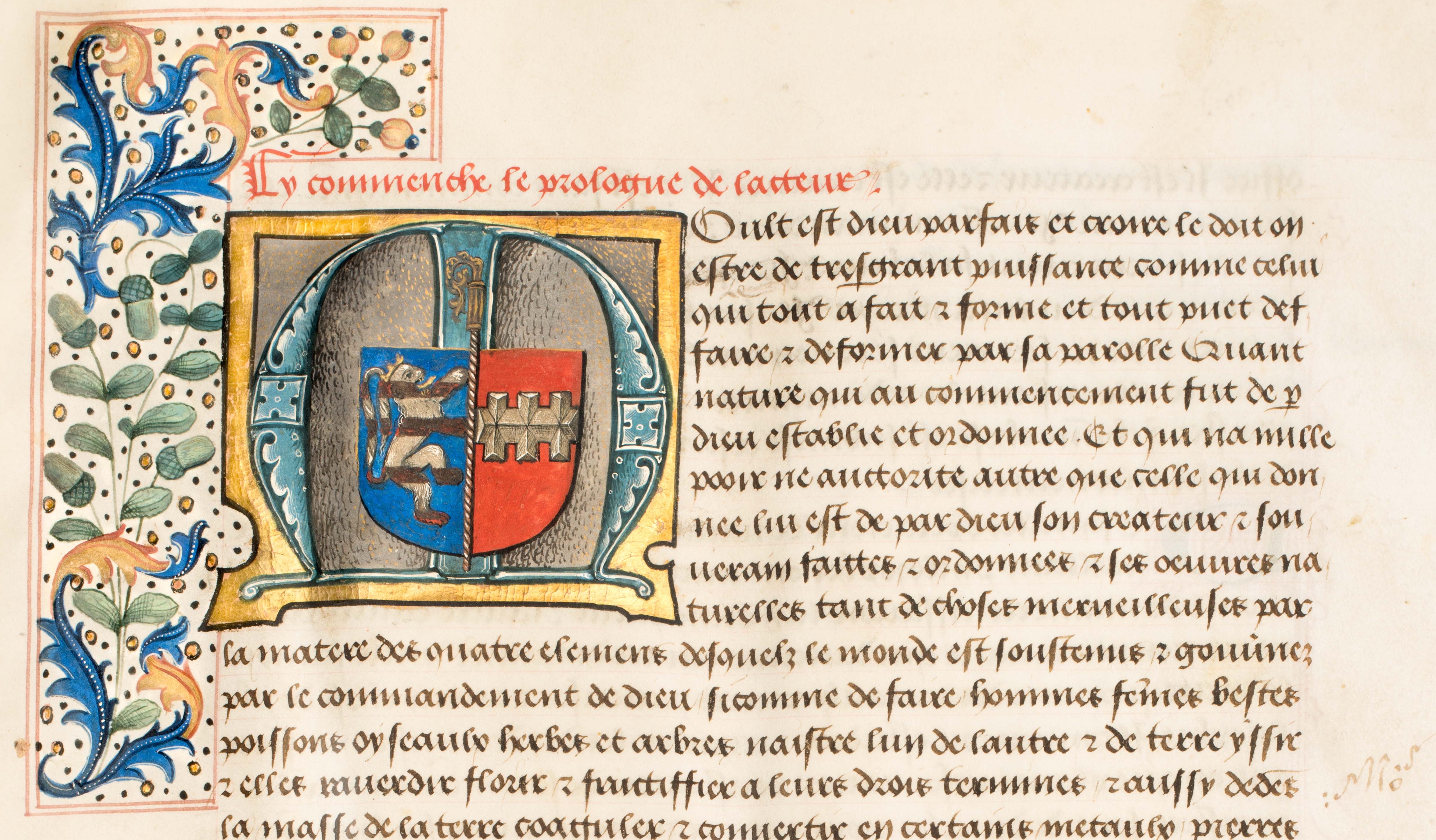

Coat of arms of Raphael de Mercatellis, abbot of St. Bavo in Ghent, in a manuscript containting: Jean d’Outremeuse (1338-1399), Le Tresorier de Philosophie Naturelle des Pierres Precieuses. – Ex divina philosophorum achademia secundum nature vires ad extra chyromanticie diligentissime collectum, and four full-page miniatures, three dealing with the Gods of Antiquity, the fourth containing a typological biblical allegory.

Raphael de Mercatellis (1437-1508) – one of many (some 26) bastard children of the duke of Burgundy – was one of the most important Renaissance bibliophiles of the Low Countries. He inherited his love for books from his father, Philip the Good (d. 1467), and shared this with his half-brother, Antoine the "Grand Bâtard" (d. 1504). Mercatel, born in Bruges, grew up to be an established diplomat and a wealthy churchman. Since 1478 he was abbot of St. Bavo’s in Ghent, a powerful Benedictine abbey that has not survived the ages. What is left of his library, however, now counts as "Flanders’ cultural heritage". The manuscript we present here is quite fascinating and contains, among others, the only text the abbot owned that was written in French. All of his books were in Latin; as Raphael disliked printed books, he owned mainly fine, handwritten and often, illuminated texts.

Our codex consists of three sections, two of which were made around 1484 – these will not detain us here. The abbot’s coat of arms, his – still unexplained – device, L.Y.S., and two ownership inscriptions leave no doubt that the book was made for him. The works are also recorded in an inventory made in 1572, some fifty years after the abbot’s death.

Four alluring, intriguing miniatures were added to the book, that – similar to the rest of the manuscript – were likely created in Bruges. Originally, however, these miniatures formed no part of any of the works in this codex and it remains a riddle as to why they were added, unless it was only for their beauty and interesting stories. They are witnesses of grand projects that were left unfinished when Mercatel died in 1508, and of which several other single leaves have been preserved. The miniatures show the continuing interest for the stories of Antiquity, retold in word and image by every generation. Here we present only one of them, while two others will follow in a second blog.

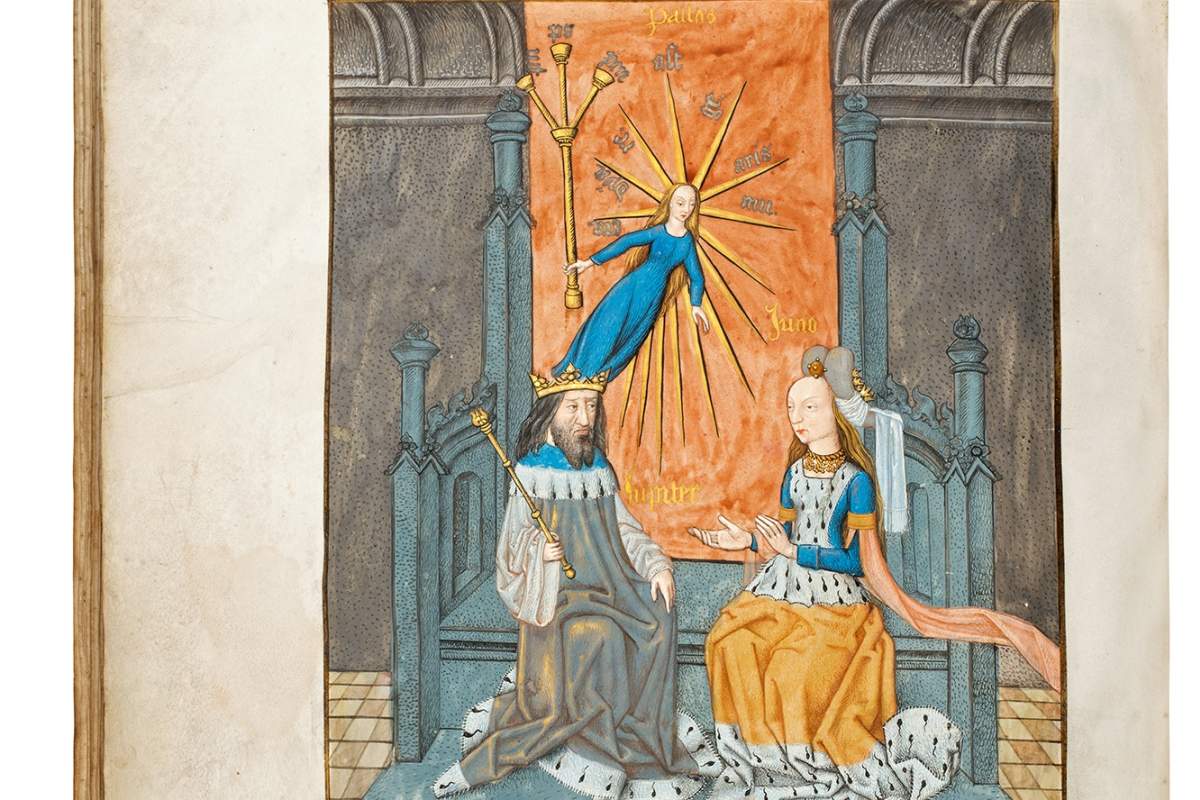

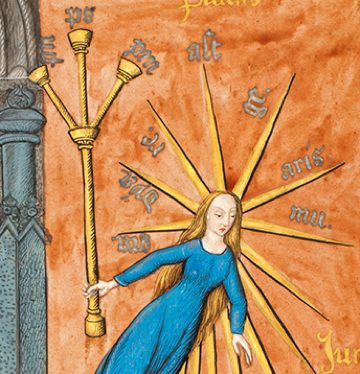

The Birth of Pallas Athena from Jupiter’s head in Mercatel's codex. Athena was often given the forename Pallas, after her childhood friend who, by mistake, died by her hand. The name Pallas taken by Athena refers to her affection and remorse. As she remained untouched by man, Fry quotes some "who maintain that she should stand as a symbol of feminine same-sex love” (Fry 2017, p. 88).

While giving birth, Jupiter and his wife Juno (not Pallas’s mother) are seated on a throne supported by Intelligentia (eagle), Voluntas (pelican feeding its young), and Memoria (griffin), known as the three powers of the soul, which are also virtues related to the Trinity.

Emerging from her father’s head, Pallas holds a sceptre, the three branches of which are marked with PN (Philosophia Naturalis), PS (Philosophia Supernaturalis), PM (Philosophia moralis). Golden rays emanate from her head symbolizing gra(mmatica), dya(lectica), re(thorica), geo(metrica), aris(metica), and mu(sica): the seven liberal arts of classical Antiquity. Mercatellis also owned another book with an illumination portraying the same subject (Ghent, Cathedral, ms. 16a, f. 8).

Although Pallas was born in full armour (conforming to literary tradition and illustratively described by Stephen Fry), the radiating girl here emanates knowledge instead of warlike aggression. The girl is shown as the symbol of wisdom, directing education, knowledge and philosophy. Due to her singular birth from the seat of thought, Pallas presides over Sapientia, a virtue that can lead the human mind to knowledge of the Divine. Pallas impersonated Sapientia, knowledge of the eternal principles of the divine sphere to which man aspires. Only Divine inspiration, emanating from "she" who is eternal wisdom, can lift one above oneself. Wisdom, "more beautiful than the sun and above the arrangement of the stars" comes first – has been sought after by those mystics who long for meaning.

This miniature made for Raphael de Mercatellis presents a fascinating medieval adaptation of the story and function of Pallas. Here, the illuminator (or an earlier advisor) incorporates classical mythology into Christian theology. It certainly calls for more research on the interests of the extraordinary Flemish abbot as reflected in his famous and valuable books.

More on Antiquity, Jupiter and his wife in part two of this series.

See our video presentation of this manuscript here.