Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 1: Initial M with coat of arms of Raphael de Mercatellis

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 123v: three large hands and a Tabula caracterum planetarum

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 124

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 133v: Jupiter and Juno on their thrones, Pallas being born from Jupiter’s head

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

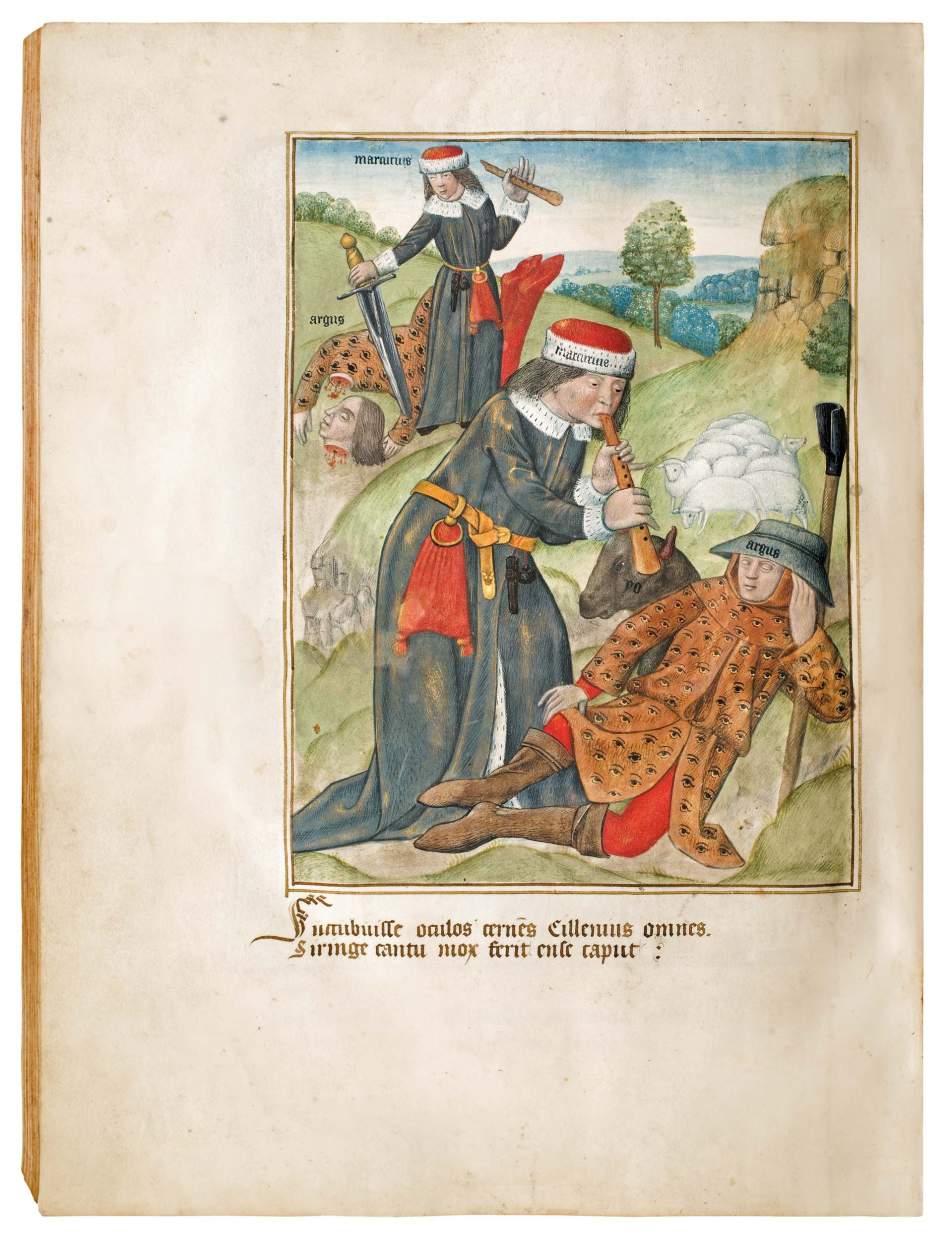

f. 135v: Juno and Argus with Yo.

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 136v: Ark of Covenant with the Nativity

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

fol. 124v

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

Hide caption

Mercatellis composite codex:

Jean d’Outremeuse, Le Tresorier ... des Pierres Precieuses; Ex divina philosophorum ... ad chyromanticie

Flanders, Ghent-Bruges, dated 1484

363 x 267 mm, 137 leaves, 21 coloured drawings

and 4 additional full-page miniatures

Hide caption

This work is now sold.

This compelling, composite codex was made for Raphael de Mercatellis (d. 1508), a natural son of the duke of Burgundy, abbot of the abbey of St. Bavo in Ghent, and one of the most important Renaissance bibliophiles of the Low Countries. The book contains the abbot's coat of arms, motto and ownership inscriptions, saying it was acquired by him in 1484.

The first text is the Tresorier de philosophie naturelle des pierres precieuses written by Jean d'Outremeuse of Liège (1338-1399). It concerns a synthesis of medieval knowledge of gems followed by recipes for making them. The work is the oldest known, systematic book on various processes related to stones, crystals, and gems, important to the work of goldsmiths, jewellers, and stone-cutters – high-ranking medieval professions. It is a rich source for ways to colour glass – techniques not only of great importance for those counterfeiting gems but also for those involved in making stained glass. It was not s pure mineralogical treatises but also describe fabulous materials, symbolic values and astrological associations of certain gems. This is a quite rare text and an important a witness to the history of the Mosan region of Liège, centre of mining and city of origin of the author. Remarkably this was the only text in the library of the learned abbot that was written in French.

The second text deals with chiromancy, divination by reading palms illustrated by 21 coloured drawings. The ‘science’ of chiromancy claims, through the study of the palm of the hand, to be able to characterize the person to whom the hand belongs and to foretell his future, a practice found all over the world. As Mercatellis preferred to have manuscripts above printed books, the text was specially hand copied for him after an early printed edition. Earlier, the Church had disapproved of this practice as superstition and chiromancy was classified as a forbidden magical art. But palmistry flourished again in the Renaissance: Leonardo da Vinci had such a book in his library and the work became part of university instruction for aspiring doctors in arts and medicine.

Four fabulous, full-page miniatures added at the end of the codex refer to other texts. The first shows Jupiter and Juno, seated on thrones supported by Intelligentia, Voluntas and Memoria. The last miniature represents the Ark of Covenant with the Nativity, connecting the Old and New Testaments. The second and third miniatures represent the mythological story of Io and her warder Argus as told in the Metamorphoses by Ovid. Several illuminators worked for the abbot and are collectively called 'the Masters of Raphael de Mercatellis'.

Mercatellis' library contained more than 100 manuscripts, of which some 65 have been identified. Nevertheless, new discoveries - as the present codex - or identifications are still made. As almost all of his manuscripts were made to order at high cost and date from the years 1473-1505, his collection offers fascinating testimony to book production and art history in Flanders. The abbot’s manuscripts provide us compelling insight into his interests as a man and a bibliophile.

Read more about this manuscript in our series of blog posts, and in our Spotlight on Burgundy in the Middle Ages, and in our Spotlight on Medieval Medicine.