Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

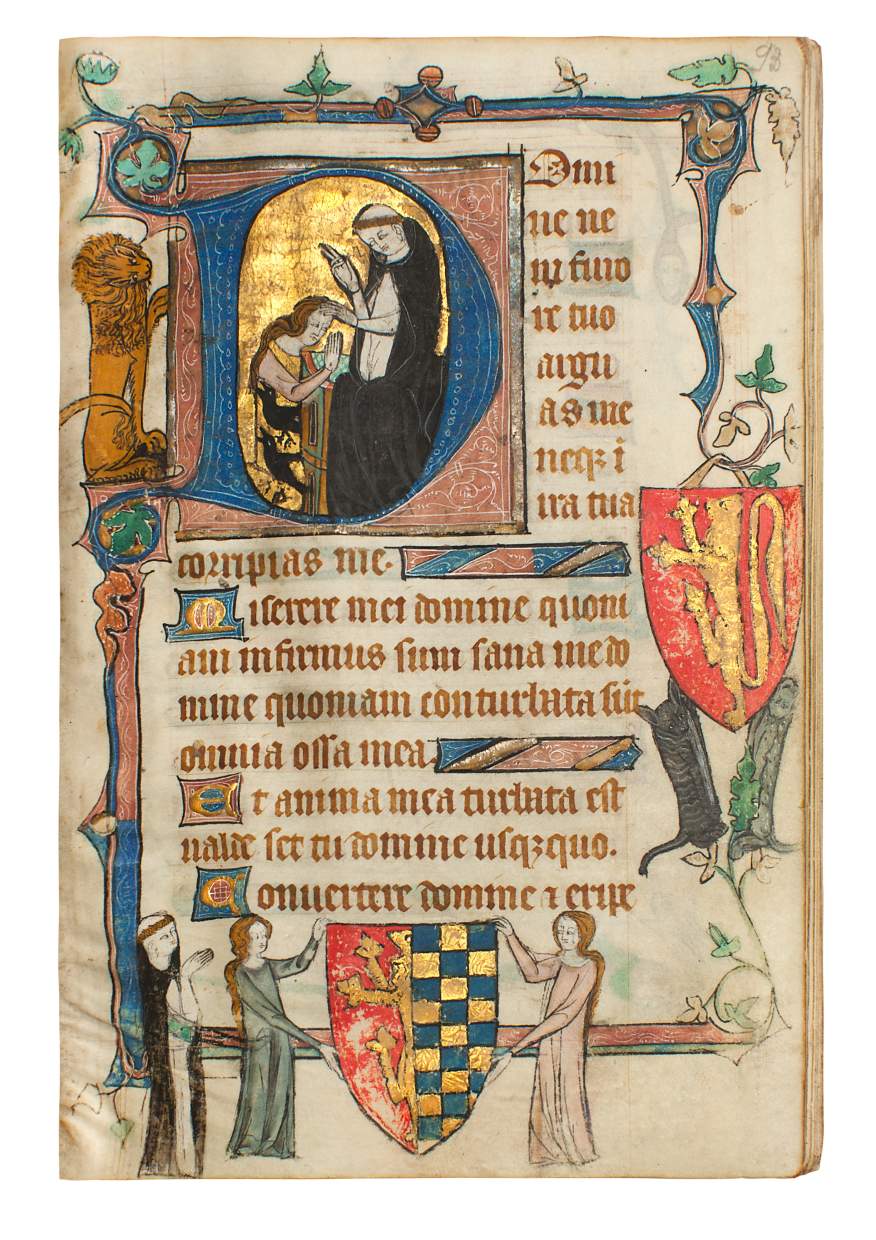

fol. 49v: Visitation

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 49v: Visitation

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 153: Office of the Dead: Job on top of a dunghill

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 6: Calendar – November, slaughter of an ox

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 119: The three Marys mourning

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 41: Annunciation

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 69v: Adoration of the Magi

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 17: The Holy Ghost in the form of a dove emerges from the clouds and appears to three ladies wearing dresses with the arms of the Beauchamp and Fitzalan/Arundel families

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 80v: Vespers: Funeral of the Virgin with the incredulous Jew

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 137: Virgin with Child; a lady, presumably Beatrice Beauchamp, kneels in front of them, wearing a dress with the arms of the Corbet family

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

fol. 147r: Office of the Dead: Funeral service with animals

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

Hide caption

Beauchamp-Corbet Book of Hours, use of Sarum

Manuscript on vellum in Latin and some Anglo-Norman,

illuminated by the Milemete workshop

England, London, 1328

165 x 110 mm, 194 leaves, 39 historiated initials

Hide caption

This work is now sold.

Decorated on nearly every page with a multitude of striking small miniatures, historiated initials, and bas-de-page scenes, the surprising illumination in the present prayer book includes animals, fabulous creatures, wild men, and other figures and presents a wealth of different coats-of-arms.

At the Penitential Psalms, a lady is depicted who receives absolution from her Dominican confessor: here, Beatrice Beauchamp is identified by way of her dress with the arms of the Corbet family. Another initial shows three standing, veiled women with hands clasped in prayer while receiving the blessing of the Dove of the Holy Spirit. The coats-of-arms show that the central woman is Beatrice while the two women accompanying her wear the arms of the Fitzalan earls of Arundel. This clearly suggests a blood relation between the ladies. In all, the illumination bears testimony to 8 noble families related to Shropshire county and its neighbouring regions, such as the Beauchamp of Hache, Corbet, Leyburn, Fitzalan, Fitzwaren, Warenne, Lestrange of Knockyn, and Leigh or Lye.

Made on the occasion of her second marriage to John Leyburn of Great Berwick, Shropshire, the widow Beatrice Beauchamp (d. 1347), daughter of John Beauchamp of Hatch (Somerset), was about to leave (c. 1329) the family of her first husband, Piers II Corbet (d. 1322) of Caws Castle. The arrangements of that first marriage were thus that the widow gained sole possession of the Corbet barony on her husband’s death – with the serious risk that the Corbets would lose their ancestral property when the new marriage of Beatrice and John Leyburn would be blessed with children. Beatrice’s second husband had inherited from the Lestrange family, and he now became lord of Caws in right of his wife. Because the Corbet shields and women dressed in the Corbet arms are so prominently depicted, this suggests that the female relations – likely Piers Corbet’s aunts, Alice and Emma Corbet – ordered the manuscript as a gift to maintain the bond with Beatrice upon her remarriage, wishing to remain ‘in the picture’, so to speak.

Not all of the scenes in the book are that serious. At the opening of the Office of the Dead within the initial D (ilexi quoniam exaudiet dominus, I have loved, because the Lord will hear the voice of my prayer, Ps. 114), the hollow of the letter shows a fox holding a book. He presides over the funeral of another fox; whose body lies covered by a shroud on a bier while two hares and two wolves function as pallbearers. A dog, a rabbit, and a stag have joined the procession. This scene seems to refer to the mock-funeral of Renart the Fox as it is told in the Roman de Renart. Such mocking images must have had a wider appeal beyond amusement: the contrast between the real and fabulist world (as Renart faked his death) reminds the reader of the importance of sincere devotion. In the lower margin, two wild men hold the arms of the Leyburn family.

Four artists collaborated in the illumination of this manuscript. They are all associated with the so-called Milemete Group who were active in London in the 1320s and named after the Treatise by Walter of Milemete that was written for the young King Edward III (c. 1325, Oxford, Christ Church College, Ms. 92).

Read more about this manuscript in our Spotlight.