Artworks

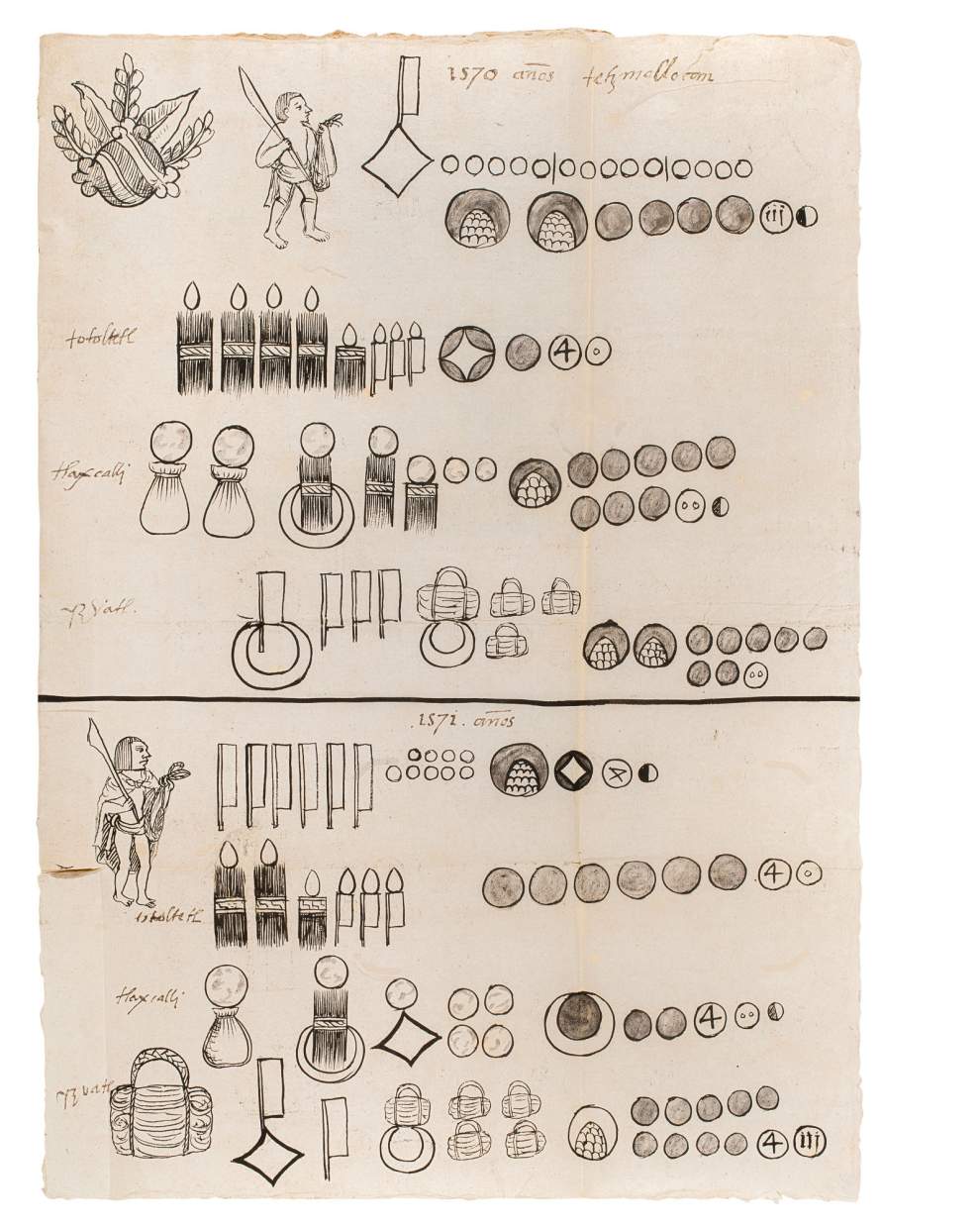

The San Salvador Huejotzingo manuscript, made for the governor and mayors of Huejotzingo. Illustrated manuscript in Spanish and Huejotzinca pictographs on paper by at least two hands.

Mexico, Huejotzingo, 1571.

This work has been sold.

Dated to 1571, the manuscript at hand is soundly attributable to the Huejotzingo region based on its pictographic tradition, the use of numerals, representation of people, place glyphs, and the signatures of indigenous authorities, which correspond to the same signatures on other documents. This manuscript constitutes a new contribution to the visual vocabulary of the region with pictorial representations not found in other codices from the same region. Adding further interest, there are two names included for local artists, perhaps pointing to those who drew this manuscript’s pictographs.

This manuscript records two pleitos (lawsuits) brought about by the indigenous people of San Salvador, a village in the bishopric of Tlaxcala to the south of the capital of Mexico and close to the city of Puebla, against their vicar, the canónigo Alonso Jiménez. To facilitate the process of Christianisation after the Conquest, the Spanish divided New Spain into different areas, assigning each one to be governed by a different religious order. The area where San Salvador is situated was allocated to the Franciscans.

The present manuscript record of this San Salvador pleito was made in 1571 by the request of the governor and mayors of Huejotzingo, the administrative capital responsible for San Salvador and where the pleito was eventually heard. It arose when a visiting inspector (visitador), who was an apostolic notary and interpreter sent by the authorities of Huejotzingo, arrived unannounced in 1570 on a vista secreta and discovered the exploitation to which the indigenous people were subjected. The inspectors went to the bishopric of Tlaxcala to denounce the canon Alonso Jiménez, who served as evangelizer in the village of San Salvador.1 In the lawsuit, the indigenous locals levelled accusations against the canon, covering a wide range of grievances, including: mistreating and harassing various local nobles and commoners of this district, requesting work from various artisans of the village without paying for their services or only paying half of what was owed, taking more than the amount of corn to which the church was entitled, charging for woollen blankets (which he was obliged to provide for free), profiting from the indigenous collection of cacates (a kind of nut) and salt and also from the textiles and ropes woven by local women, not paying his cooks, and finally, charging for officiating marriages, baptisms, and burials. The pleito, apart from the official Spanish documents which include the canon’s self-defence and signature, consists of indigenous testimonies in Náhuatl with their signatures and six remarkable drawings by at least two different hands.

The pleito ends with two long verdicts declaring the canon guilty of some of the charges and ordering him to pay two pesos of gold to be shared out among the people who had provided him with six jarrillos (jars) of oyamelt (oil), made from a fir tree in the area. He was also required to pay six pesos of gold each to two indigenous workers who had served him, Felipe Ortiz and Juan Milan. However, he was acquitted of the majority of the accusations including those of the two painters, who had already declared to the visiting inspector that they had received their full salaries.

ILLUSTRATION

1-2. Drawings one and two represent an indigenous figure called ‘the guardian’ accompanied by a rich collection of symbols that represent the different amounts of maize tortillas, eggs, and other foodstuffs, with the names (also written in Náhuatl) which had been given to the canon from 1570 to 1571. Drawn on European paper.

- Drawing three represents the carpenters with their faces and names who took part in constructing the local Church and making the canon’s furniture. Drawn on bark paper.2

- Drawing four represents two frames of paintings, probably as a representation of full paintings and, significantly, the names of the two painters, Marcos de San Lucas and Joachin Gutierrez who were also suing the canónigo. Each frame, of varying quality, is attributed to one of the two painters, with the value in ‘tortillas’ that each one was worth. Drawn on ‘amalt’ paper.

- Drawing five seems to represent pictogram measurements and a painting. Drawn on bark paper.

- Drawing six represents the layout of the Church with the different chapels, their names, and their measurements. Drawn on European paper.

The rapid expansion of the Spanish evangelisation had required the employment of numerous artists to fill the new temples with representations of Christian stories in a visually accessible way to the indigenous inhabitants. However, since it soon became impossible to have sufficient numbers of Spanish artists to carry out the work, as it was the case in San Salvador, the Spanish resorted to local artisans. It is probable that Marcos de San Lucas and Joachin Gutierrez are the local artists who made this manuscript’s drawings. They were tlaiculos, the indigenous artists who painted murals and codices before the Conquest and continued during the 16th century. References by name to these painters are rare and especially so as their names are attached to a particular work. As in all churches, the paintings for San Salvador, whose subjects are described in the plan of the church, had to follow European styles and conventions but, as the survival of these drawings show, the parallel culture and visual language in which the local artists communicated was still alive and very much in use. It was also a language that Spanish officials were willing to accept in a legal document. The symbiosis of the two cultures is also evident in our pleito in the figure of Pedro Collacos, who signed many of the affidavits and who was the Bishop of Tlaxcala’s translator of nahuatl, a nahuatlato. He was regarded a mestizo and was married to an indigenous woman with whom he had three daughters.

HUEJOTZINGO, A MESOAMERICAN ALTÉPETL

In Mesoamerica, particularly in the Nahua towns, the concept altepetl was used to designate the socio-political unit that prevailed in this cultural area during the post-classic period (950- 1521). Generally equivalent to a city-state, the altepetlwas characterized by being dominated by a lineage, established on the basis of a specific worldview, whose jurisdiction covered a particular territory that included a centre as a meeting place for civil, religious, and commercial events. Huejotzingo was one of the most important altepetl that existed in central Mexico since it had a proper and independent political structure and at the same time had the recognition of other señoríos, or domains, which were administered by a leader who was called tecuhtli and was part of the ruling lineage.

When the Mesoamerican peoples were subjugated by the Spanish crown in the 16th century, Huejotzingo was one of the few that managed to retain much of its territorial, economic, and political structure; as is seen in the so called códices Huejotzincas, which provide, using pictograms, a detailed record of the twenty districts subject to this altepetl. Needless to say, their respective tax burdens and their main authorities were also noted.

Today, five codices manufactured in Huejotzingo, other than the manuscript at hand, have been located; all are housed in public institutions, although there are other unpublished manuscripts in private libraries that are yet to be studied. The first of the five is known as the Codex Huexotzingo and was created in 1531; the second is called the Matrícula of Huexotzinco, dated 1560; the Codex Guillermo Tovar de Huejotzingo is dated c. 1566 to 1568; the Chavero Codex of Huexotzingo11 (1578), and finally, the Xopanaque land Codex, which was recently located in the National Library of Anthropology and History and is still to be dated.

The Chavero Huexotzingo Codex was also part of a pleito with interesting artistic similarities and was produced in the same city as the trial at hand. The Chavero Huexotzingo Codex records a pleito brought against the authority of indigenous officials accused of levying unjust and excessive taxes. In that codex, the officials, responding to a questionnaire, describe the different taxes paid by the 21 districts of Huexotzingo between 1571 and 1577: in money, maize, shirts, and blankets. The proceeds of those taxes, which were collected since 1563, were used to build a church in the San Salvador district. This could possibly be the church referred to in the present pleito.

From a visual point of view, the document on offer here allows us to learn more about unknown aspects in the Huejotzinca glyphs. From a historical standpoint, this manuscript bears witness to an event yet unknown to history, concerning the secular clergy’s abuse of indigenous people of the Barrio of San Salvador, Huejotzingo, and reveals more details about the evangelization of the Valley of Mexico’s indigenous peoples.

Mesoamerican codices are extremely rare. There are some 500 colonial-era codices in libraries, but we have been able to trace three such manuscripts on the art market.

– We are very grateful to Dr. Baltazar Brito Guadarrama of the Mexican National Institute of Anthropology and History, upon whose analysis we largely based the present description.