Artworks

The Lalaing, Livre des faits du bon chevalier Jacques de Lalaing,

Manuscript written in French on vellum, illuminated by Simon Bening and workshop,

Flanders, Bruges, written c. 1480s, painted c. 1520s.

364 x 262 mm, 202 leaves, 18 miniatures.

f. 36v: Great alarm at the court of the King of France when a tournament is announced. Jacques de Lalaing kneels before Charles, Count of Maine and the Count of St. Pol, and pleads that he may battle in their honour.

Hide caption

The Lalaing, Livre des faits du bon chevalier Jacques de Lalaing,

Manuscript written in French on vellum, illuminated by Simon Bening and workshop,

Flanders, Bruges, written c. 1480s, painted c. 1520s.

364 x 262 mm, 202 leaves, 18 miniatures.

f. 48v: Jacques de Lalaing encounters Boniface of Sicily at a joust before the Duke of Burgundy and his young son, the Count of Charolais – the later Charles the Bold

Hide caption

The Lalaing, Livre des faits du bon chevalier Jacques de Lalaing,

Manuscript written in French on vellum, illuminated by Simon Bening and workshop,

Flanders, Bruges, written c. 1480s, painted c. 1520s.

364 x 262 mm, 202 leaves, 18 miniatures.

f. 151: The battle at Locres (East Flanders)

Hide caption

This deluxe manuscript was probably written in the 1480s, left unfinished and illuminated some thirty years later by Simon Bening and his workshop. Most likely this was a commission of Charles I, seigneur de Lalaing (d. 1525), who was the second cousin of the the book's hero.

The text and its magnificent images illustrate the main exploits of Jacques de Lalaing (1421-1453), the most exemplary Burgundian knight and one of the best tournament fighters ever. He was the oldest of four sons of Guillaume, lord of Lalaing and Bugnicourt, high bailiff of Hainaut and governor (stadhouder) of Holland (d. 1475). An elegant and chivalrous fighter, Jacques grew into a successful champion of tournaments. Knighted in the service of Duke Philip the Good in 1445, he was elected to the Order of the Golden Fleece six years later. He was killed in the revolt of Ghent at the siege of Poeke castle (1453) – the moment just before the impact of the canon ball that took his life is illustrated in this codex.

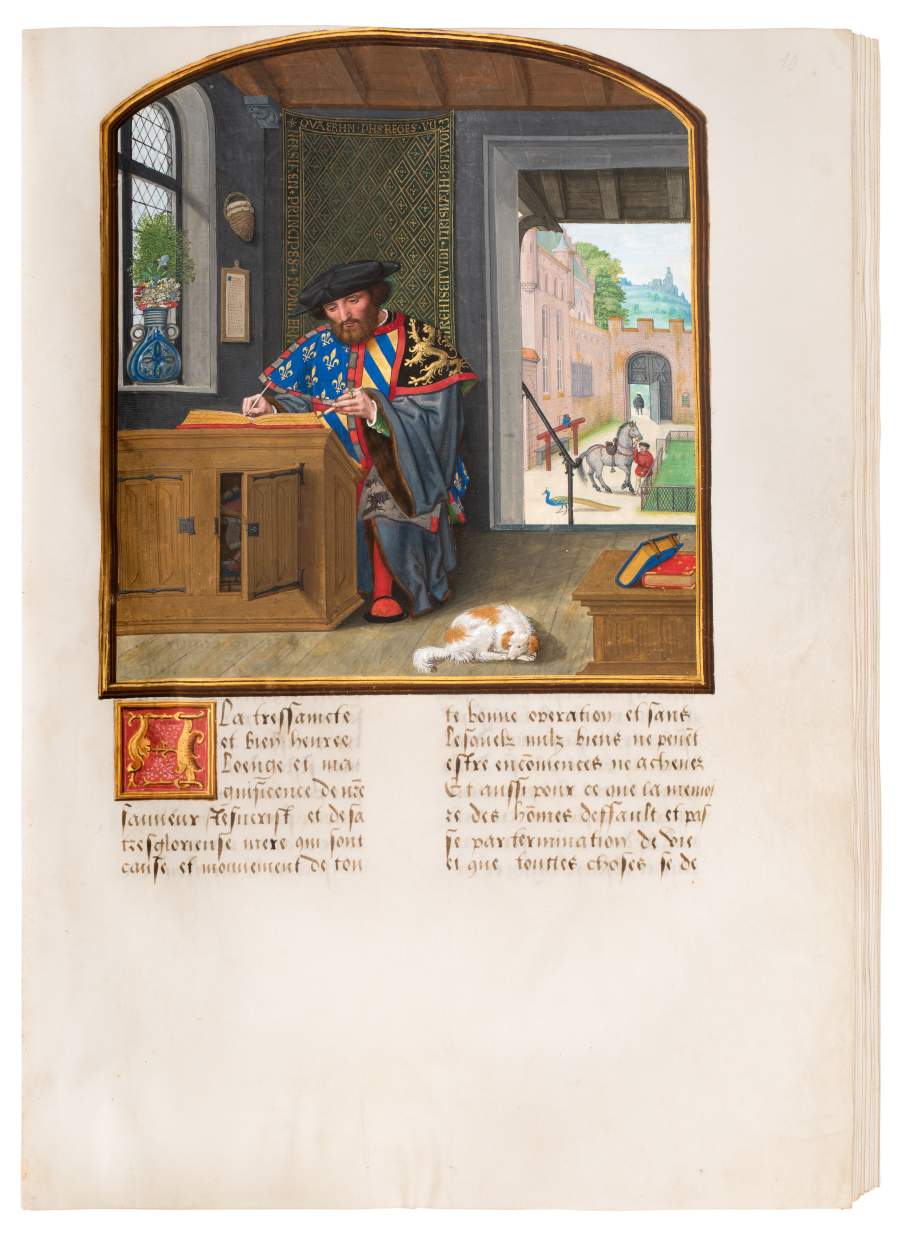

This codex is, without doubt, the finest Burgundian manuscript (of seven surviving), illuminating Lalaing’s military exploits. The miniatures offer fairly literal interpretations of the key episodes of Lalaing’s career and heroic deeds. The superb large portrait at the opening is the key to this book. It represents the author, a man in the prime of his life, in his study at work. He is the herald of the glorious Order of the Golden Fleece, Toison d’Or – identifiable by his splendidly ornamented tabbard, a costume with the coat of arms of Toison d’Or. The texture of his rich costume is incredibly lifelike. The writer’s handsome face is individually modeled and recalls other portraits painted by the renown Flemish illuminator Simon Bening. The supposed author of the text, Jean Le Fèvre de Saint Rémy was – until his death in June 1468 – Toison d’Or, King of Arms of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Both Toison d’Or and the Bon Chevalier had been close friends.

The memory to Jacques de Lalaing's life was, presumably, put to writing upon instigation of his father Guillaume de Lalaing, who had lost all his sons before he reached old age. The Livre des Faits de Jacques Lalaing gained the young knight eternal fame. The text may have originated c. 1465-1470, a few years before Guillaumes’s death, but the dedication manuscript seems not to survive. Both Charles I and his brother Antoine I de Lalaing owned manuscripts of the Livre de Faits de Jacques de Lalaing, but we only know of three that were made on paper. Was the present book on vellum perhaps the family's best heirloom? As their is no coat of arms or provenance note, we can only guess at how this magnificent codex was handed down and survived throughout the ages.

Read more about this manuscript in our Spotlight on the Splendour of Burgundy, and in our Spotlight on the Crown of a Career.

This work is now in the collection of the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles.