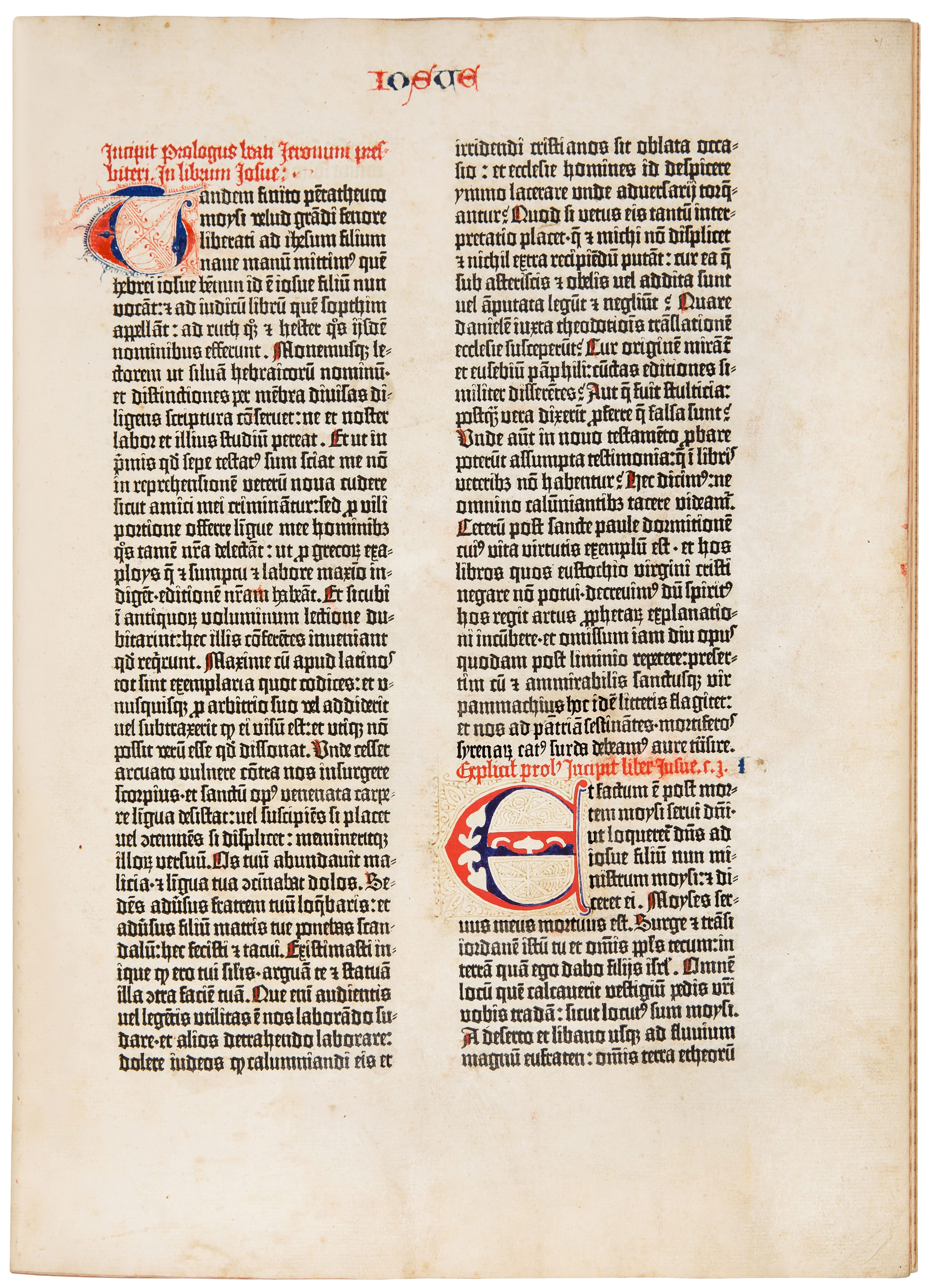

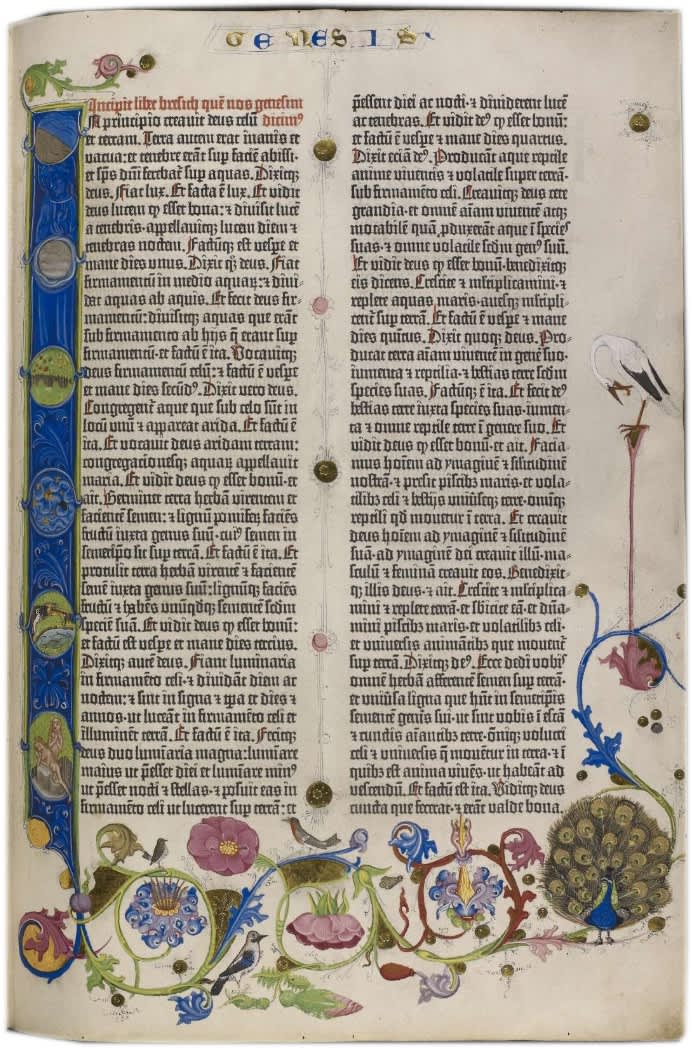

The first book to be printed with movable type printing was a Bible - the Book of Books. Around 1454/55, Johannes Gutenberg from Mainz set about the daunting task of printing a Bible with 324 pages in folio format. Gutenberg's Bible was printed in Latin. Not long after his first printing adventure, other printed Bibles followed in Latin and in German.

Obviously, public demand was great.

Gutenberg Bible (fragment), sold by Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 1)

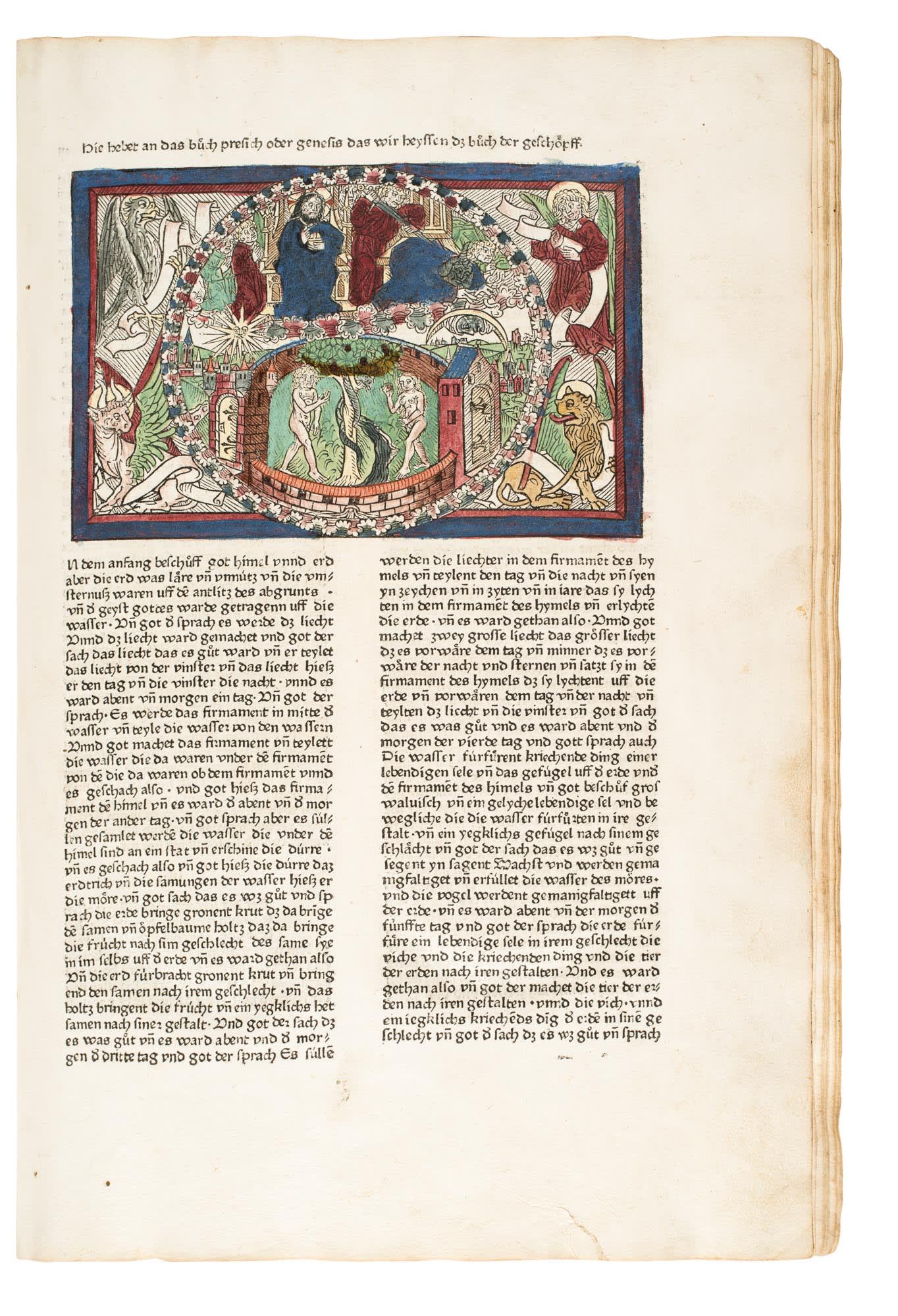

Relatively soon after Gutenberg printed his first (and only) Latin Bible, other Latin Bibles from other workshops followed. Then, c. 10 years after Gutenberg's breakthrough B42 (B for Bible and 42 for the number of lines per page or column), Johann Mentelin from Strasbourg printed the first German Bible around 1466. This was the prelude to a sequence of no less than 13 Bibles in High German, which were published until the end of the incunabula period (which ended December 31st, 1500). The second German Bible was also printed in Strasbourg by Mentelin c. 1470. These first two editions were without illustrations.

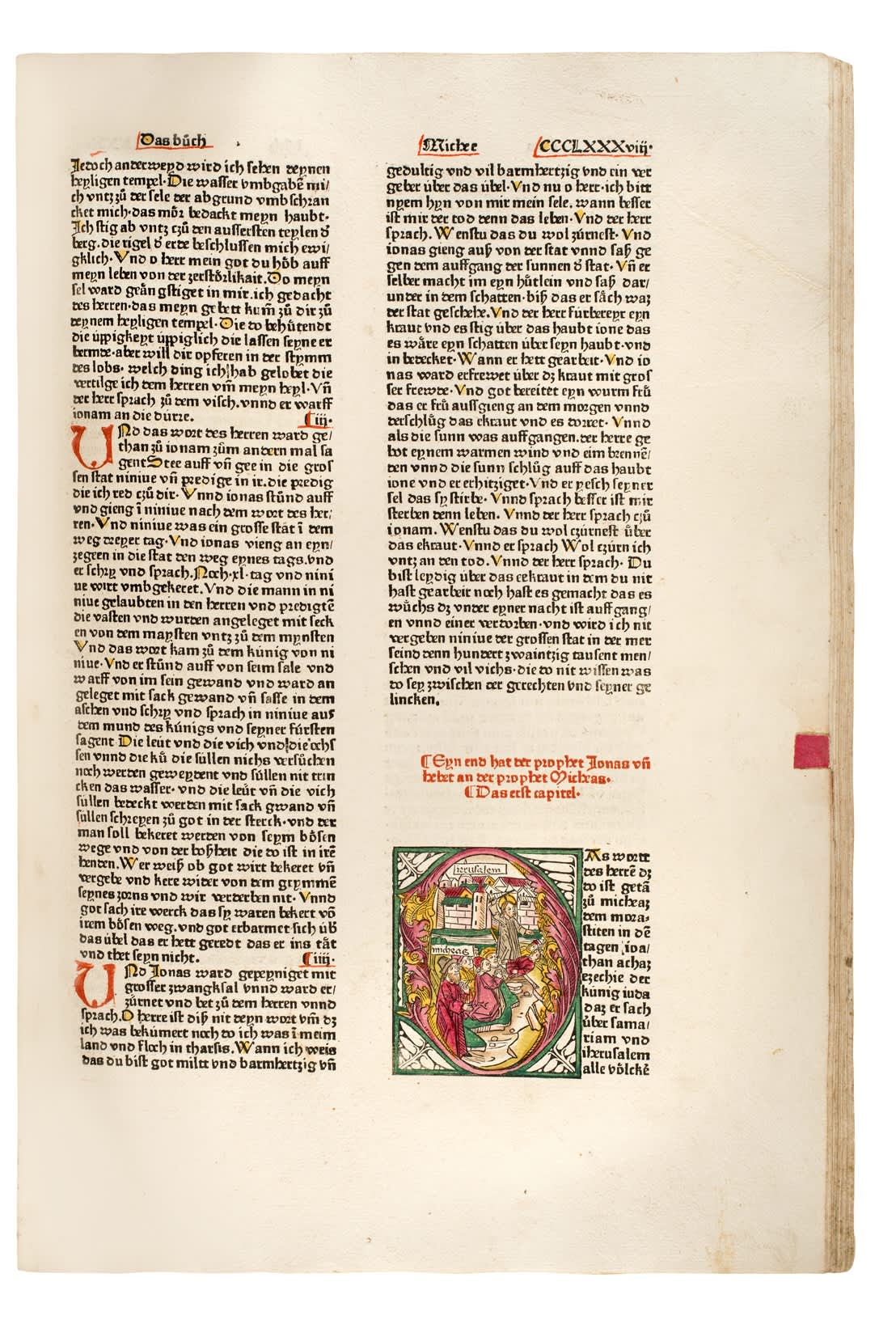

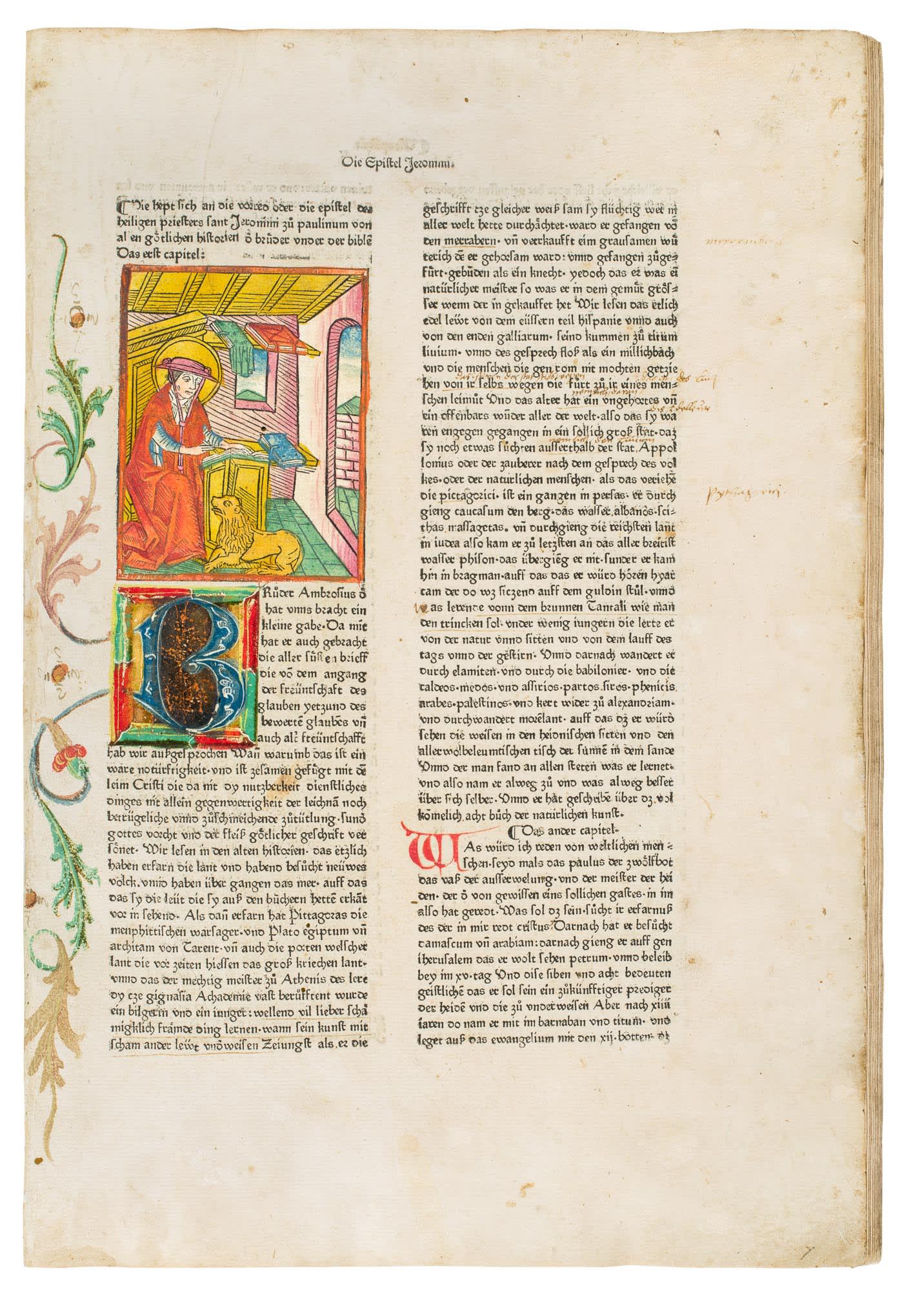

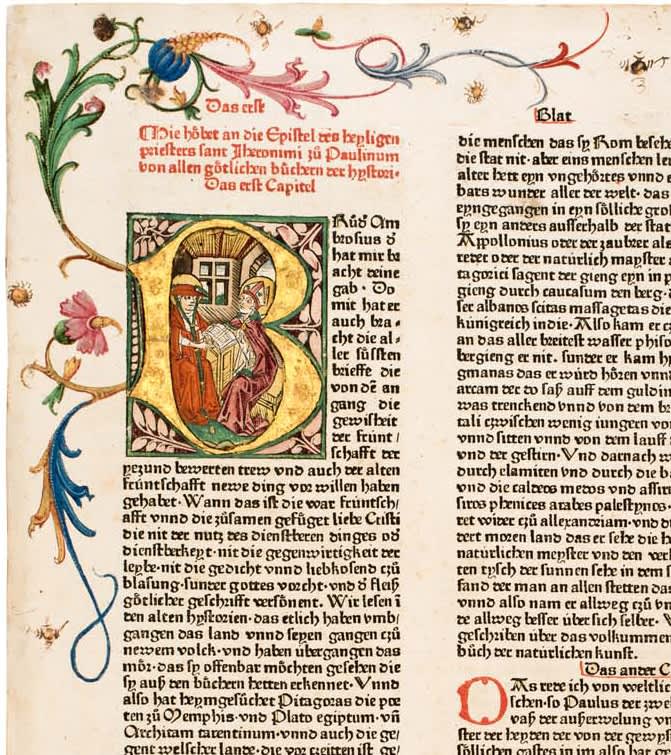

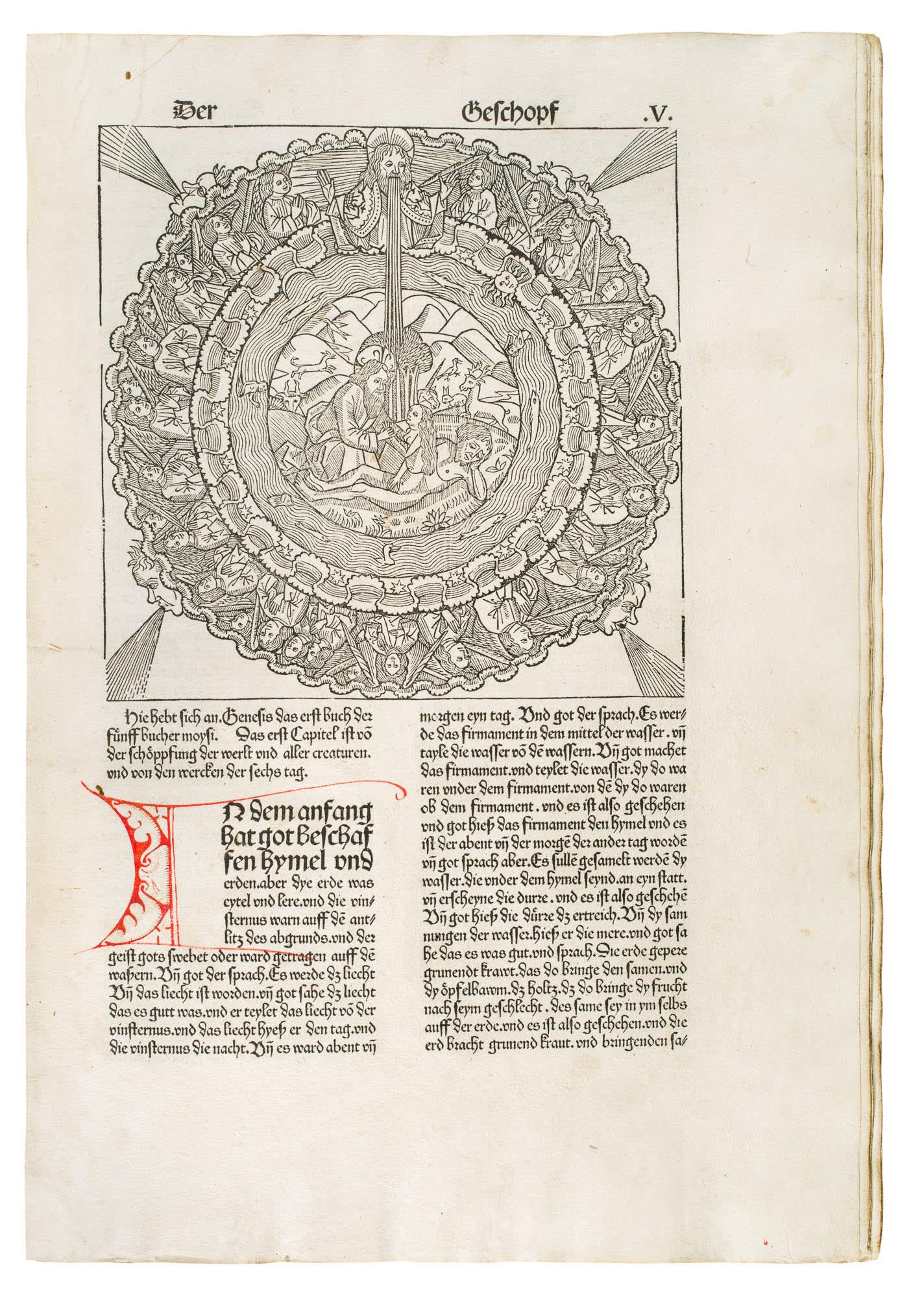

G. Zainer, Third German Bible , sold by Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 4)

G. Zainer, Third German Bible , sold by Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 4)

The third German Bible was made by Günther Zainer in Augsburg between 1474 and 1476. This edition was improved with the addition of 73 woodcuts. Zainer's German text was revised and corrected compared to Mentelin's first two editions. Günther Zainer is an interesting example of a craftsman who was already active in the book trade as a scribe before the invention of movable type printing. He trained as a typesetter in Strasbourg (probably with Mentelin) and finally became one of Augsburg's most successful printers.

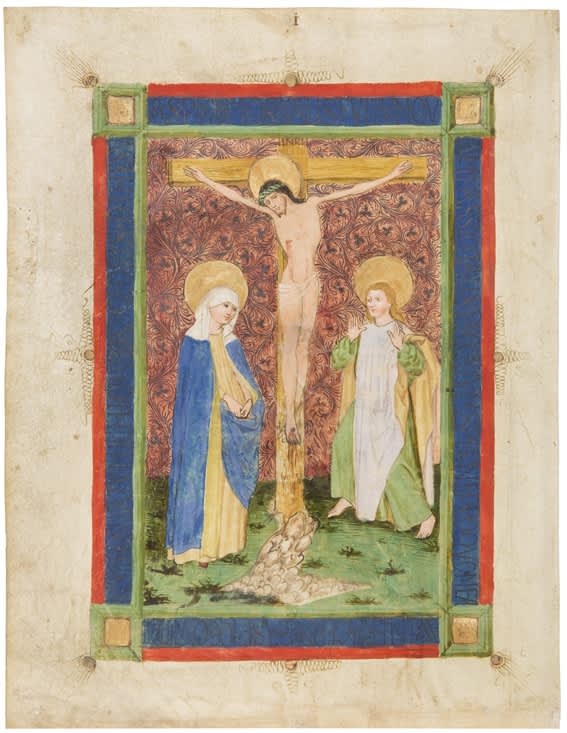

Johann Bämler of Augsburg had a comparable career. He also trained with Mentelin in Strasbourg, and worked as a scribe and manuscript illuminator before he opened a prosperous print shop in Augsburg.

Crucifixion from a Missal manuscript by J. Bämler or his atelier, avaliable at Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books

The fourth German Bible is also by an Augsburg printer: Jodocus Pflanzmann. He was notary and procurator at the clerical law court. He ran a modest press producing mainly small publications, such as indulgences.

J. Pflanzmann, Fourth German Bible , avaliable at Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 5)

It was formerly regarded as the third German Bible, but since Pflanzmann was only secondarily a printer, it seems unlikely that he ventured such risky and costly task of publishing a huge Bible before Zainer. It is reasonable to assume that after Zainer's Bible sold successfully, Pflanzmann followed suit. He was also closely connected with the printer's workshop at the monastery of Saints Ulrich and Afra, which could have received financial support from Abbot Melchior von Stammheim.

The matter of financial support plays an important role in the history of early printing. Gutenberg had a wealthy backer in Johann Fust, without whom this ambitious project would have been impossible to accomplish. However, Fust also caused Gutenberg's bankruptcy, poverty, and misery, from which he never recovered. When the first Bible edition did not sell as hoped, Gutenberg had to hand over all his material to pay his debts. Henceforth, Johann Fust and his son-in-law Peter Schöffer acted as printer and publisher using Gutenberg's typesets.

The Gutenberg Bible did not sell as rapidly as was expected, this was because buyers initially harboured mistrust against the printed word. Not everyone was thrilled by the fact that 100 Bibles could be printed in the same amount of time that a scribe needed for a single manuscript. Some even suspected that the devil might have a hand in the process! But even those who were not worried about Satan's contribution to printing activities often preferred the hand written book. For this reason, printed books were often embellished and illuminated to resemble manuscripts. In some cases, it can be difficult to tell magnificently illuminated prints and manuscripts apart.

Handsomely illuminated B42 (Gutenberg Bible), Berlin Staatsbibliothek, SMPK

Woodcut, gilt and illuminated, Third German Bible, sold by Dr. Jörn Günther Rare Books

Hopefully it is clear from these explanations that even a copy of a printed Bible was a very costly purchase. It is unthinkable that these books were available to the low- or middle-income groups of the population. Books remained luxury objects even after the invention of movable type printing, acquired either by churches and monasteries, or by wealthy individuals.

To modern audiences it may appear as though biblical texts translated into German would make them more accessible to readers without knowledge of Latin or trained in theology. However, this was not the case until much later, when Martin Luther published his New Testament in 1522, a translation that actually corresponded to spoken German. The pre-Lutheran German Bibles were so closely and literally based on the Latin text of the Vulgate that they were practically incomprehensible to a person who did not understand Latin.

For theologians and clergy, however, the printed Bible (whether in German or Latin) was a great improvement, because now they could rely on uniform versions of the text that were not contaminated by errors and nonsensical abbreviations made by unfocused scribes. This certainly simplified theological discussions and exchanges about the texts of the Bible.

J. Sensenschmidt, Fifth German Bible , Dr. J. Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 7)

Johann Sensenschmidt printed the fifth German Bible between 1476 and 1478 in Nuremberg. The colouring of this copy already betrays a tendency towards a more efficient, less individualised production. This inclination continues throughout the 15th century. However, one of the renowned printers in Nuremberg, Anton Koberger had an exciting business plan. His clients were able to decide if they wanted a splendidly coloured copy or if they preferred a cheaper black and white version. He also exported unbound and unaltered copies to other regions and countries. This would permit the local buyers to have their copies furnished due to the regional taste.

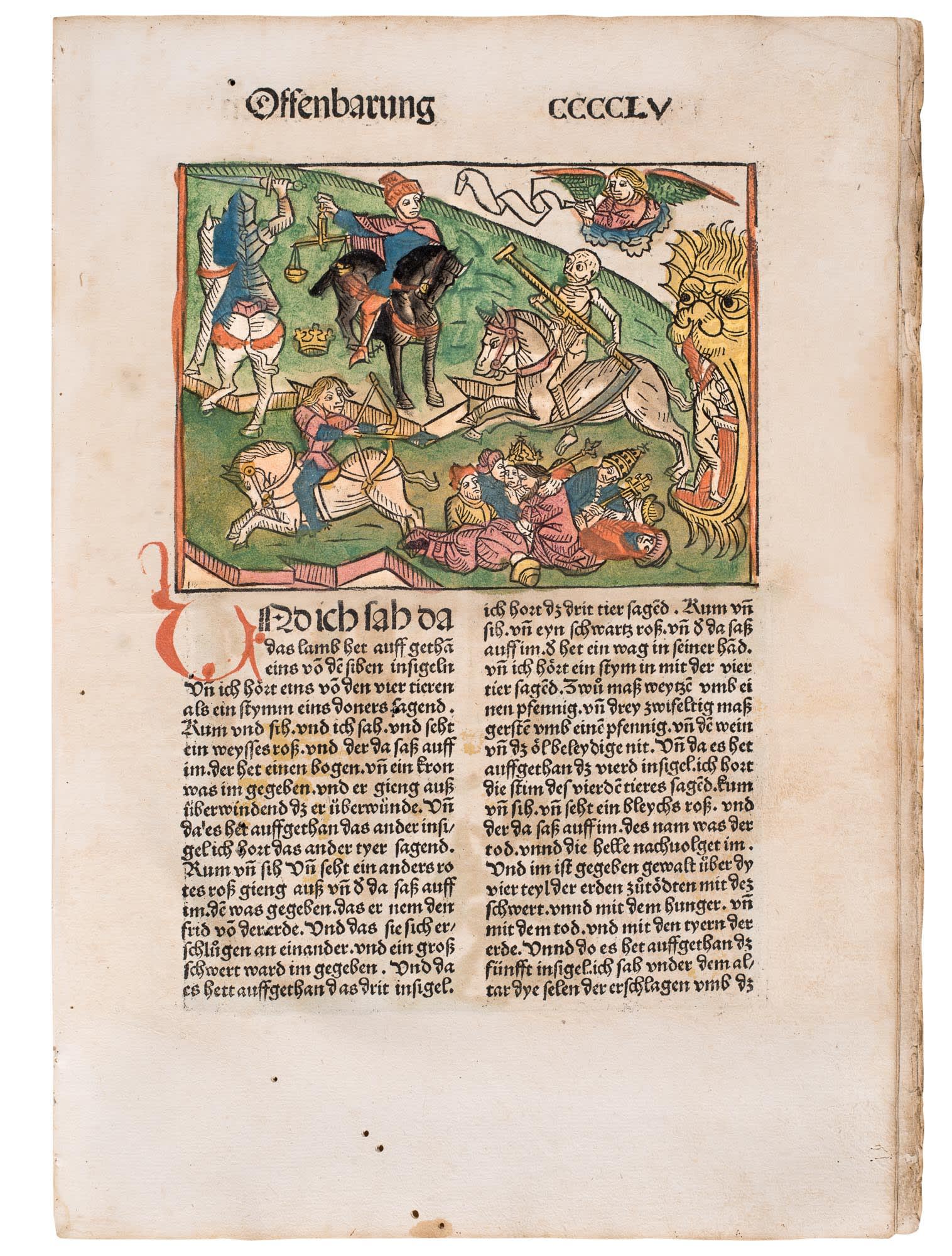

A. Koberger, Ninth German Bible, 1483 , Dr. J. Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 9)

A. Koberger, Ninth German Bible, 1483 with luxury colouring , ex-Dr. J. Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 8)

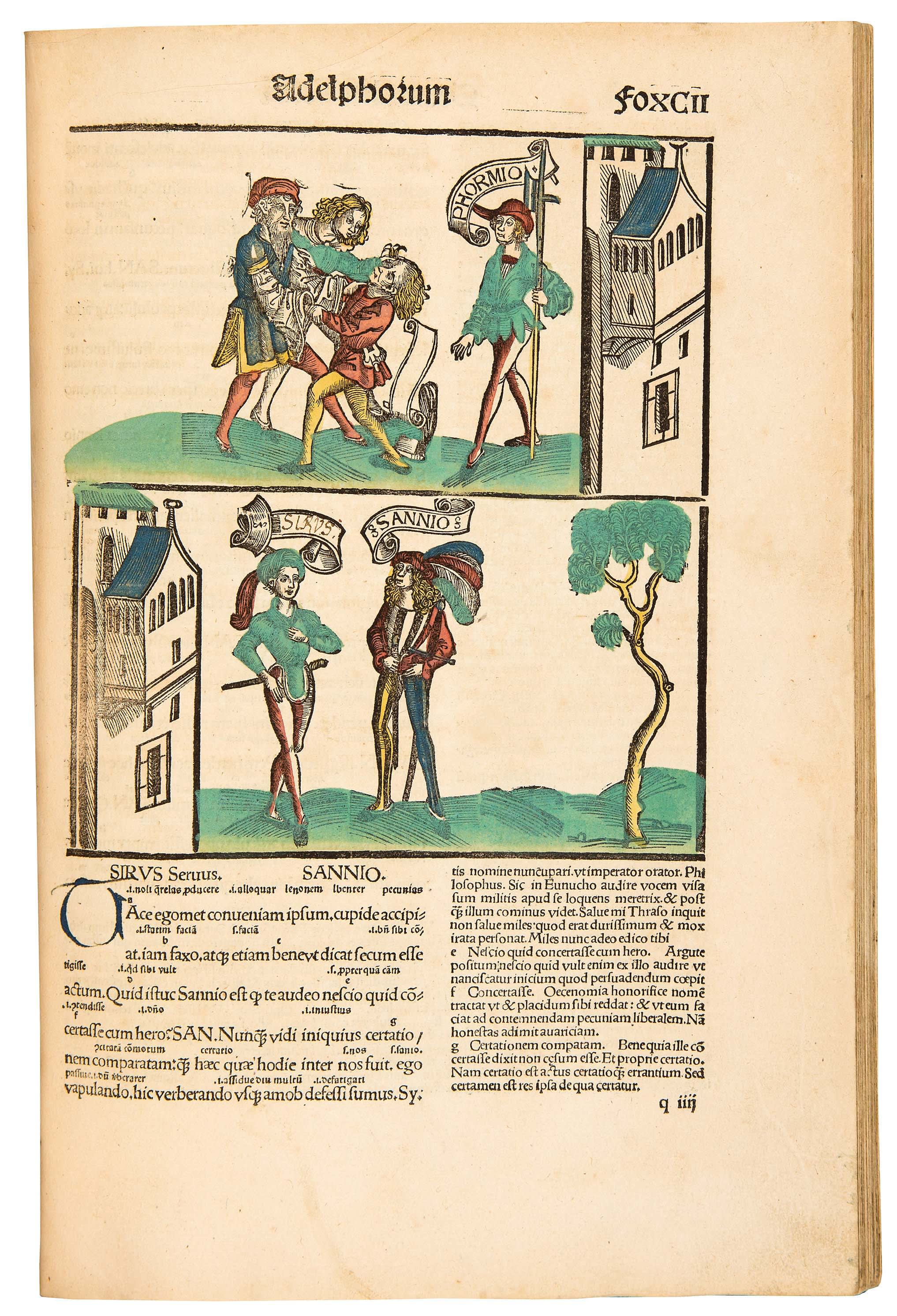

The final German Bible that we would like to introduce here, was printed by Johann Grüninger in Strasbourg in May 1485. It is the tenth Bible in High German and Grüninger's first illustrated book. It is considerably smaller (278 x 193 mm) than the other books discussed here, which often exceeded the height of 40 cm. The smaller format made Grüninger's Bible a handy family Bible. He utilised Koberger’s woodcut models and had smaller copies made.

J. Grüninger, Tenth German Bible, 1485, Dr. J. Günther Rare Books (cf. cat. 12, no. 10)

Grüninger did not employ any illuminators in his workshop. He left it entirely to his clients to have their copies embellished. This is the case in the example above. In later printed works, especially in Terence's theatre plays, Grüninger improved his practice of simplifying and rationalising the printing material. He developed a system of set pieces for the illustrations that could be freely combined. This also simulated the stage decorations of real theatres. His innovative system was adopted and utilised by other printers relatively quickly, and thus the printing arts advanced.